Bonus Book Chapter: The Closing Arguments at Jens Soering's Trial

A new chapter I'll be adding to my upcoming German book.

Introduction and Housekeeping

First of all, I’ve gotten some inquiries from people who want to support my work financially. So far with this blog, I’ve decided to make it free for everyone, with no paywalls. One main reason is that more often than not, my posts are intended to correct a false or misleading assertion by one Söring or one of his supporters. As Jonathan Swift said: “Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it.”

But that was centuries ago. Now the truth can not only go online minutes after the falsehood did, sometimes the truth can come out before the falsehood. I don’t want to interrupt that process by a paywall. Further, I don’t rely in income from my journalism to pay the bills, and sometimes months go by without anything intereseting happening in the Söring case.

However, it does take quite a bit of time and effort to write these posts. Also, Söring has sued me once for what I wrote on a blog (spoiler alert, I won, thanks to the peerless lawyering of David Ziegelmayer), so I know that one of Söring’s many lawyer friends may be reading anything I post here. So instead of a paywall, I decided to create a Ko-Fi account. This allows you to make a one-off donation, no subscriptions or repeat charges:

I’m using Ko-fi because it generally seems to have a good reputation and I’ve donated with it without getting spammed by promotions. (If you have any other services to recommend, I’m all ears.) Of course you can donate anonymously, in case you don’t want to be publicly associated with (as the trolls might put it) the relentless six-year campaign of character assassination and defamation which I have been waging against Jens Söring, a bespectacled German nerd whose only crime was being seduced by that Jezebel Elizab!tch.

So if you’ve enjoyed some of my posts and are inclined to send me a little Trinkgeld of whatever amount feel free to do so, it will be much appreciated.

As the German-language version of Martyr or Murderer, I am considering a few options. I have I used Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing for the English-language version, and that was obviously the most convenient, since Amazon handles the book production for you and the product looks reasonably classy. However, I’m also looking into other avenues.

As I went through the manuscript, I realized I hadn’t given the closing arguments at Soering’s trial enough attention. I decided to include a new chapter specifically addressing those arguments, which will appear in the German version and the updated English edition. I have included many direct quotes to try to capture the style of the two clashing lawyers. I then provide my own analysis at the end. Please note this is just a draft; you are free to quote it if you like, as long as you make that clear.

Commonwealth v. Soering: The Closing Arguments

The court convened for closing arguments on June 21, 1990. Closing arguments are a key phase of a criminal case. To be sure, the judge will warn the jury that closing arguments are just that – arguments. They are not evidence, and the jury should not consider them as such. But they offer lawyers an opportunity to present an overall survey of their case, synthesizing discrete pieces of evidence into a coherent whole.

Closing arguments are governed by strict rules. Lawyers must refer only to evidence presented during trial and “reasonable inferences” which can be drawn from it. They may not refer to anything outside the evidence unless it is a matter of general common sense or common knowledge (objects fall downwards, feathers usually come from birds, etc.). The prosecution may not comment on the defendant’s failure to testify or mention any of the defendant’s previous crimes or bad acts unless this information was already allowed into evidence. Rhetorical exaggeration is permitted, but dehumanizing insults are not. By convention, lawyers will not object during each other’s closing arguments unless a lawyer says something extremely inappropriate.

Before the arguments, though, there were preliminary matters to address. The parties gathered around the bench to haggle over details of the “jury charge”, the written instructions which guides the jury’s deliberations. After the final formulation was agreed, the judge reads the charge to the jury. A jury charge in an American trial is not exactly easy reading. Here is the part of the jury charge Judge Sweeney read to the jury which defines first-degree murder:

“The Court instructs the jury that the defendant is charged with the offense of first degree murder. The Commonwealth must prove beyond a reasonable doubt each of the following elements of this crime: First, that the defendant killed Derek Haysom, and second, that the killing was malicious, and third, that the killing was willful, deliberate and premeditated…. The Court instructs the jury that willful, deliberate and premeditated means a specific intent to kill adopted at some time before the killing, but which need not exist for any particular length of time.

The Court instructs the jury that malice is that state of mind which results in the intentional doing of a wrongful act to another without legal excuse or justification at a time when the mind of the actor is under the control of reason. Malice may result from any unlawful or unjustifiable motive, including anger, hatred or revenge, Malice may be inferred from any deliberate, willful and cruel act against another, however sudden.”

That is a lot to absorb. Virginia was one of the original thirteen American colonies and has a centuries-old legal tradition. As in Germany, the definition of murder in Virginia contains elements which are centuries old and uses antiquated language such as “malice”. To make sure they understand the law, the jury is provided with the charge in written form to guide their deliberations. They can also ask to inspect any evidence or have portions of the trial testimony read to them. They can ask the judge questions when they are deliberating, but before answering, the judge must consult lawyers for both sides. Sometimes the parties can agree on a clarification. If not, the judge will simply tell the jurors to apply their common sense and the ordinary meaning of the words in the charge.

After the charge is read to the jury, the prosecution presents its closing argument. The prosecution goes first because it bears the burden of proof. After the prosecution makes its argument, the defense presents its argument. After that, the prosecution may then present a “rebuttal argument” addressing the points the defense made. The defense may sometimes ask for permission for a “sur-rebuttal” responding to the prosecution, but generally the judge will stop matters after the rebuttal by the prosecution.

Below is a summary of the closing argument for the prosecution, the closing argument for the defense, and the prosecution’s rebuttal. These summaries are drawn from the original trial transcripts and videotapes. Closing arguments can sometimes be disjointed, as the lawyer may suddenly remembers something and and switch thoughts midstream. That shows through in these summaries. I have made slight grammatical corrections for consistency and ease of reading.

Prosecution Closing

Jim Updike presented the prosecution closing. Updike first introduces himself to the jury and thanks them for their patience. He then turns to the definition of murder, spending most of his time on the terms “premeditated” and “malice”. He notes that under Virginia law, there is no set time limit: a few seconds is all it takes to “premeditate” a killing. Updike also informs the jury that the mere fact that a defendant has drunk alcohol or used drugs before the act does is not a defense, unless the defendant was so intoxicated they could not form the intent to commit the crime. Updike notes that he does not anticipate the jury will face problems applying these standards, since the killer’s actions here were clearly premeditated.

Updike then moves on to the evidence against Söring. Updike returns to a core theme several times in his closing: Soering, he argues, had planned the entire weekend to be an alibi for murder.

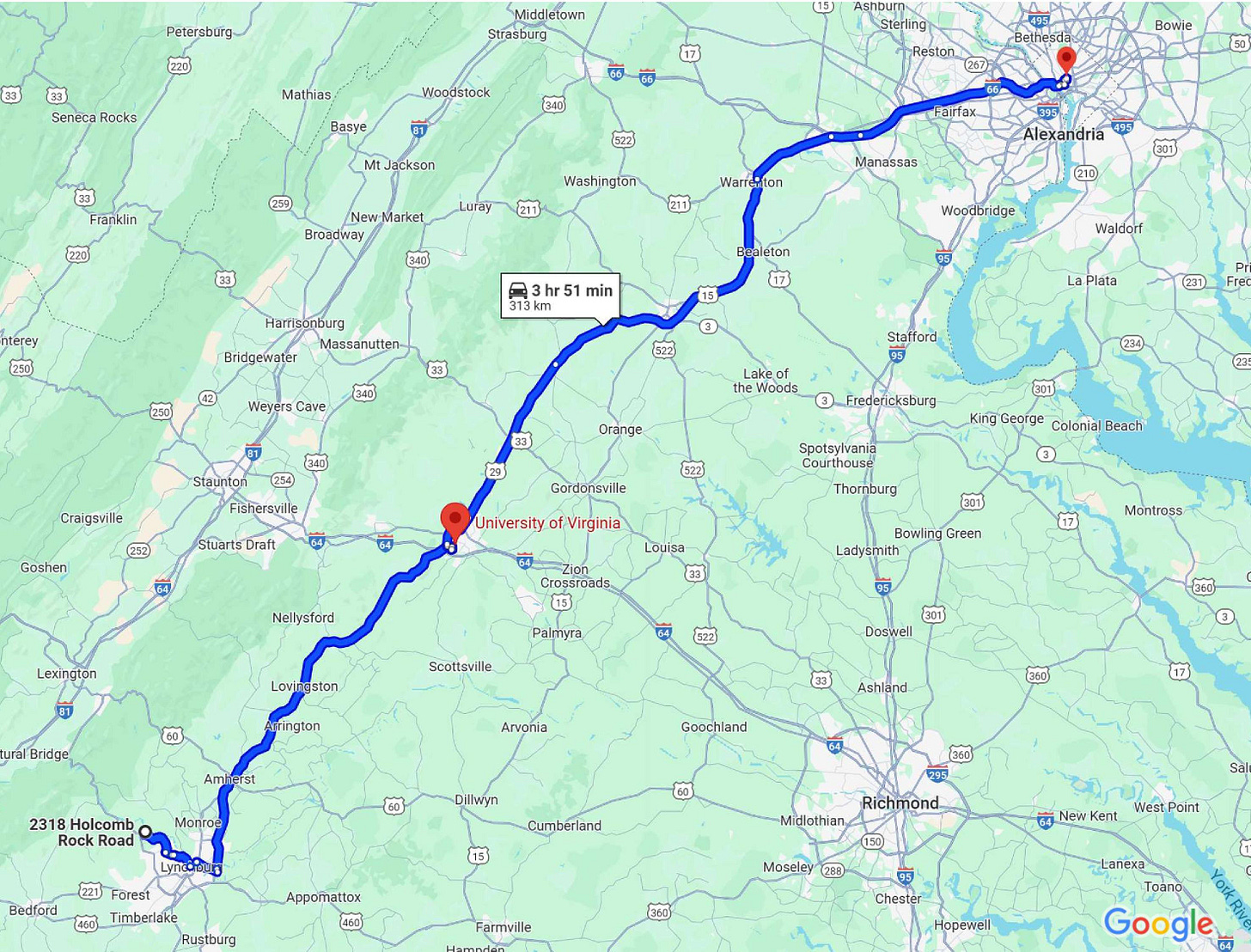

If Soering had merely wanted to talk to Derek and Nancy Haysom, he could have done so any time by driving from Charlottesville; the journey would have taken just 90 minutes. [This map illustrates Updike’s point:

Instead, he and Elizabeth drove in the opposite direction for 3 hours to reach Washington. Why? Because he wanted the entire weekend to be their alibi. This is also why he kept the tickets from their dinner and movie on Friday. This, Updike argues, shows premeditation. As for malice and intent to kill, Updike appeals to reason: “Now what intent in the world can any human being have when virtually cutting a man’s head off, except the intent to kill him.”

Updike also notes the cruelty of the killer’s actions: “Once all of this was done, all of the injuries were inflicted, Nancy Haysom is lying there bleeding, her life blood oozing away, she dies, this man is cold blooded and calculated enough to roll her over so that he can wipe the area where he did the stabbing to make sure that there are no fingerprints, no footprints; conceal evidence. These two people lying dead in this fashion, and the murderer returns, thinking not about them, thinking of himself. Now we'll continue with the defendant himself, no remorse, gets on the stand and gives a performance that you all saw, lies about it. [Soering deserves] life imprisonment.”

The Christmas letters show premeditation going back even further, because, according to Updike, the letters show the pair had already discussed getting rid of the Haysoms even before the letters were sent:

“Well Elizabeth, she had written in her Christmas letter, remember, my father rolled down off the cliff. [Soering] admits in his testimony, they were talking about that, that's a possibility. Piranhas in the bathtub, bombing the house, fire. Elizabeth writes in her letter, the Christmas letter about my mother almost fell into the fire. You see, they're talking all kinds of possibilities, it's still early in the game yet. But they're talking about the death of two people, the murders of them.”

He goes through Söring’s confessions and points to the corroboration. He said the Haysoms were drinking, they were. His remarks about where people sat at the table matched the crime scene. There were consistent shoe patterns throughout the house. We can’t say exactly what the shoes were, Updike admits, shoes but they’re consistent.

Updike then hypothetically reconstructs the crime: Soering slashes Derek’s throat first. Nancy, after a moment’s shocked hesitation, runs toward the kitchen. Söring knows there is a phone in the kitchen because he’s been spent time in that room. Soering grabs Nancy from behind while Derek is incapacitated and slashes her throat. Derek climbs back up, leaving a bloody handprint on a chair, and resumes his death-struggle with Soering, who finally manages to subdue him, albeit after being injured himself. Soring then inflicts additional stab wounds to make sure neither Derek nor Nancy could possibly survive:

“Jens Soering…can't let Derek tell anybody about what he's done to Nancy and he can't let Nancy tell anybody about what he's done to Derek, and he was there to kill them and he intended to kill them, and he's gone and did what he was going to do and what he intended to do, and he did a right good job at it.”

Updike now turns to the issue of the bloody sockprint. Using foot impressions from Julian Haysom, Mary Fontaine Harris, and Elizabeth Haysom for comparison, Updike argues Soering is the best match. Updike reminds the jury that Elizabeth willingly gave samples, but Söring refused. Updike admits investigators were slow to start investigating Söring but invokes Söring’s comment about yokels as a sarcastic explanation: “idiots” that we were, we didn’t focus in on him for several months, “but even a blind pig finds an acorn sometimes”.

In October 1985, Soering decides he will drive to Bedford for an interview, believing he can “charm us country boys”. During that interview, he boasts that he can “talk or write his way out of anything”. But afterward, Söring becomes concerned, realizing that Ricky Gardner “is not too happy with what he heard” because it does not fit “common sense”. Soering lies to the police to delay them, and then on “October 12th, he is hot to trot to get out of this country, the case is about to be solved, remember that that's written in the diary. Perhaps Jens's fingerprints on the coffee mug; the diary that they both wrote together.“ Soering killed the Haysoms because “He didn't want Derek and Nancy to be the center of [Elizabeth’s] life, he had to be. That need to be the center of her life had been destructive, violently and brutally destructive.” Here, Updike echoes Dr. Showalter’s assessment from Elizabeth’s 1987 trial: Soering killed the Haysoms primarily as an act of control, not of love.

Updike then addresses one of the logical inconsistencies in Söring’s English confessions: “If the man wanted to take it on himself, why didn't he? Why in the very beginning of the interview say, ‘I want to talk about Elizabeth's involvement.’? Well he wants you to believe that’s the last thing that he wanted to talk about, he wanted to protect her.” Yet his own actions belie this, Updike insists.

Updike describes what he believes is the real reason for Söring’s confession:

“You see, what happened, ladies and gentlemen, what triggered this, and the thing that's responsible for all of this really is when that Keith Barker [Söring’s English solicitor] on the morning of Thursday, June 5, 1986, walked into that cell and tossed down in front of them that newspaper from England that talked about the voodoo and all that stuff, that put this fear, an ultimate fear in Jens Soering. Because he realized then, he knew that we had evidence to incriminate him. He admitted that from the stand, that's why he left this country to begin with.

He knew at that point that the police officers had all these writings that I talked about that he wrote, the ultimate weapon against the parents, having the dinner scene planned out, we had all of that… And he said [to himself] the only way for me to get out of this and to save myself is to admit to what they got on me,I killed them, but this voodoo, I didn't do any kind of voodoo.”

Updike then drew a contrast with Elizabeth Haysom:

“And Elizabeth Haysom, regardless of what you want to say about her, or think about her, because she's a murderer, she has been convicted of first degree murder by her pleas as an accessory before the fact; whatever you want to talk about, it carries the same penalty of 20 years to life, it's murder under Virginia law. She walked into this courtroom, and she accepted responsibility for what she did, and that was she manipulated this man, she wanted him to kill her parents, he did do that.”

After confessing, Soering starts to have second thoughts:

“Now it's July [1986], and he started thinking about what he's done. Well he's told the truth…. And he started thinking about his plans, how is he going to get out of it, and he starts writing Elizabeth letters, saying make contacts with any lawyers, any high people in the United States, anybody in the Home Office. And he follows, and if I can quote him directly as far as the words he used, he said, ‘I can't tell you that this is going to do you any good, but what I want you to do -- so I'm asking you to save my ass in the hope that somehow it will help save yours’. Now is that the statement of a man, ladies and gentlemen, who has made the ultimate sacrifice for somebody else?”

Updike then delivers his final remarks:

“But if there were any possible mitigation(it) would be to try to get on the stand, show some remorse, and try to explain why he did it. Instead he gets up here and he lies to you. And I'm not going to comment any further on what he did on the stand, but let you all rely on what you all heard and what you all saw. A person able to do these acts is cold blooded, calculated, mean and vile. This man can get on the stand, first degree murder charges, talk about this, try to put on a little performance, try to talk had his way out of it and laugh about it. Cold. He needs to be convicted of first degree murder and sentenced to life imprisonment, that's the only justice. Thank you.”

Overall, this is a solid, conventional closing statement. Nothing Updike said was out of order, so there were no objections from Neaton or Cleaveland. Updike focuses mainly on inferences about Söring’s state of mind, pointing to the cold-blooded nature of the offense. His other main focus is the crime-scene evidence, which not only corroborates Soering’s confessions but yields further insights into how premeditated and cold-blooded Soering’s actions were. Updike demonstratively ignores Söring’s trial testimony, except to mock Söring’s arrogance. This is another rhetorical technique: By not even engaging with Söring’s trial testimony, he sends the subtle signal Soering’s version was so implausible that it did not even merit a response.

As the trial tapes show, Updike delivered the closing in a dramatic fashion, using gestures and tone of voice to emphasize his points. From a German perspective, this can seem flashy and even manipulative; German lawyers are supposed to be sober and objective at all times, although they can occasionally get quite animated. All American lawyers who intend to practice in courtrooms train extensively in effective communication skills. After all, they are presenting their arguments to a group of laypersons who would be bored or alienated by a dry, didactic presentation. All talented trial lawyers strive to make their arguments to the jury as lively as possible, without condescension. Both Updike and Neaton succeeded.

Defense Closing

I won’t be “as emotional” as Updike, Neaton promises the jury. The prosecution said the evidence was like a puzzle, but the problem is when the prosecution finds a piece that doesn’t fit, they “tailor” it so it does. It’s suspicious that the prosecution always plays down the evidence that could place Elizabeth at the crime scene, such as the Type B blood on the towel “on the wash rag in the washing machine” and the hair found in the dining room [Neaton here almost certainly means the downstairs bathroom] that “might have been trampled or might have been rolled over in blood”. The prosecution dismissed Elizabeth’s fingerprints on the vodka bottle by speculating they “might have been there for a long time”, but how can we be sure?

This case presents two “diametrically opposed” stories: Either Soering committed the crime, or “Elizabeth Haysom did it, and more likely with one other accomplice at the crime scene”. The evidence implicating Elizabeth at the crime scene is stronger than for Soering. There was an unidentified accomplice, Neaton insists, “at large in Bedford County…or in these United States”. Elizabeth and this person committed the crime while Soering was “in Washington, D.C. running around buying tickets”.

Neaton notes that as a “former schoolteacher” he likes to use chalkboards, so he presents the jury with a placard of “seven questions” that the prosecution failed to answer. Its failure to answer these questions, he insists, establishes reasonable doubt. Going even further, he claims not only that there is reasonable doubt here, but that this is “as close to a defense being able to prove actual innocence of their client as I have ever experienced”. One evidence gap was the room-service receipts, which could have exonerated Söring if the police had timely investigated the matter. Instead, they waited too long, and the evidence was lost.

The prosecution mentioned the savagery of the crime: “I’m not here to say this is not a brutal crime, I’m not here to say there wasn’t a travesty committed upon Mr. and Mrs. Haysom, I’m not here to say that somehow those people deserved their fate.” But justice demands proof beyond a reasonable doubt. The prosecution has introduced over three hundred exhibits, “possibly as much evidence as I have ever seen in terms of sheer volume introduced”, but all of it is outweighed by the movie tickets, “which weigh little more than the air we breathe”, because they prove that Jens Söring was in Washington, D.C. – especially the 10:15 pm ticket, since whoever used that ticket cannot possibly have murdered the Haysoms. We are “lucky” to have these tickets, Neaton says, praising Söring’s father for having the perspicacity to find them in Soering’s belongings. The tickets prove Elizabeth to be the “pathological liar that she admitted she was to Jens in the letters”. What really happened is that Jens Söring bought the tickets to all the movies “at about the time that is on these tickets”.

The canceled check from the Marriott Hotel also bolsters Söring’s story, since it was cashed on March 30, 1985, “at a time when Elizabeth Haysom was on her road to Lynchburg to do away with her parents”. Jens Söring said he cashed it when Elizabeth was already gone. But the police didn’t care. They never bothered to pursue this evidence until far too late: The police “even waited five months or so after they indicted them before they even sought to go get this stuff.” Neaton makes one of the standard “tunnel vision” arguments drilled into every defense lawyer: “What I'm saying to you is they made up their minds before they had all the facts, and that is the problem in this case, ladies and gentlemen.”

Elizabeth’s prints are on the vodka bottle, but the prosecution never asked her how they got there. The reason, Neaton concludes, is that those prints were left on the night of the murders. If the prosecution had found Soering’s prints on the bottle, they would have trumpeted this news from the rooftops. Elizabeth is right-handed, but the prints on the bottle are from her left hand. That, Neaton argues, is because they were left when she was trying to wipe her prints off the bottle. The fingerprints on the bottle may not prove Soering’s innocence alone, but they are another indicator of reasonable doubt.

Even the prosecution’s own expert admitted a sockprint could not be tied to any one person, unlike a fingerprint. And if you look at LR3, „Elizabeth’s footprint fits right inside that“. Neaton derides Hallett’s testimony:

„And they bring in some guy who isn’t even an expert who puts this thing [the transparency] over this print, ignores the fact that the big toe doesn’t line up, and ignores this part of the big toe that hangs over, ignores this part of the heel that’s much longer than the print on the floor, and then ignores the fact that it is smudged all to heck, and how do you know what part of this is the sock and what part of that that’s the foot?”

Neaton then asks “Bill” (i.e. William Cleaveland) to help him show the jury a comparison of Elizabeth’s foot to LR3 and argues that it fits Elizabeth better than Söring. The prosecution tried to downplay the Type B blood (Elizabeth’s blood type) in the kitchen, but she “is the only person in this trial that’s writing ‘I wish my parents would just lay down and die, I wish my dad would drive off a cliff, I wish that I could commit voodoo on them’ okay? Does that sound like reasonable doubt to you? It does to me.”

The prosecutions suggested the small bloodstain in the kitchen it was really Type AB blood, but that argument was speculation. Besides, if it had been Type O blood, wouldn’t the prosecution have made a big deal of that? Remember, the prosecution’s theory is that Soering committed this crime alone; any evidence someone else was there should raise reasonable doubt. The bottom line is that “The killer washed the blood off of her cuts on that wash rag, and Elizabeth Haysom threw me wash rag in the washing machine, thinking it wouldn't be found.”

There was too much Type O blood at the scene, considering that the scars on Soerings’ hand were “little itty-bitty things”. The prosecution failed to analyse many pieces of potential evidence, such as knives found in the kitchen and a “heel print” found on the kitchen floor, which matches Elizabeth Haysom’s “heel width”. The prosecution collected fibers from various places in the house but they obviously didn’t match Soering, since we didn’t hear about them. There appeared to be footprint on one of slippers Nancy Haysom was wearing, but the police did not investigate further.

In the dining room, it was more likely the attack on Derek Haysom came from Haysom’s left, not from his right, as Söring claimed in his confessions. The prosecution claimed Soering had removed his own place setting from the house but presented no proof anything was missing from the residence. The assailant could have simply taken a knife from one of the drawers in the dining-room table. The ambiguous shoe impressions were just as consistent with Elizabeth and perhaps another person. The crime scene photos seem to show a switched-on lamp in Elizabeth’s room; Neaton argues this was where Elizabeth changed her clothes after the killings. Again, he hammers home Elizabeth’s unreliability: “In this case, ladies and gentlemen, you have to take the word of an admitted pathological liar, a person who has lied under oath before in order to convict my client in this case, end you have to take her word beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Turning to the discovery of the movie tickets, Söring’s father “say[s] he never had any conversations with his son about this case before his son disappeared, and…he wondered where his son had gone and for what reason.”1 The prosecution’s theory requires you to believe Söring was driving around in Virginia for more than three hours dressed only in underwear and a sweatshirt. It’s more plausible that “he wasn’t doing anything but sitting in his room waiting for his girlfriend to come back”. Elizabeth is by her own admission a pathological liar, drug abuser, and manipulator. It was easy for her to manipulate him into covering for her, “and once he agrees to do it, he’s trapped in the…web that Elizabeth Haysom was beginning to spin around him at that time. He’s trapped because he bought the tickets, and she knows it at that point. She knows that she has him at that point.”

Neaton invites the jury to make a comparison:

“Do you think that it's more believable that Elizabeth Haysom can convince this young man to go and kill her parents as opposed to just taking the blame for her, or alibi for her? I think it’s more convincing, more believable that he could be manipulated into taking the blame for it, because you read his literature, the volumes of it that he writes before and after these killings, all I'm saying to you is there is a common theme in that, and that is he's in love with this girl and he wants to protect her…. And I agree, ladies and gentlemen, that that doesn't make sense, it isn't the logical decision an intelligent young man should make, but he's 18 years old at the time when he makes this decision, he's in love deeply for the first time in his life. And he's an intelligent young man, but he's not a mature young man. He's an intelligent young man, but he doesn’t have a lot of common sense, he doesn't have a lot of experience in life that an older person would have.”

The crime must have been motivated by strong emotion, that was certainly the case with Elizabeth: “[Y]ou can almost see Elizabeth Haysom there stabbing each time, ‘I hate you, I hate you’, as she cuts the throats of both of her parents. [Söring] has no reason to do this, he doesn't need to do it. There is no reason why they can't continue their relationship in Charlottesville away from her parents, he’s met the parents one time.”

Elizabeth’s credibility is the key to the case:

“Now ladies and gentlemen, Elizabeth Haysom has to be believed beyond a reasonable doubt in order to convict my client. But my client also testified in this case, he didn't have to do that. He told his side of the story, and he got on the stand and he admitted that what he said in the past to the British police and to the German police was not true, and…he has made inconsistent statements.” But he explained to the jury “the reasons [why] he did it. And this is the first time that he's been under oath in this case, and the first time he’s had the opportunity to tell the jury what happened.”

Neaton now ties all of his arguments together:

“And in connection with the physical evidence at the scene, the prints on the vodka bottle, the slipper with the footprint on the sole that nobody cared to look at, not [Soering’s] hair in the sink, no room service tickets, the fact that contrary to what Elizabeth Haysom says, that the ticket is for 10:15 p.m., not 4 p.m., and that there is a canceled check cashed at the Marriott hotel.

You have to judge his testimony in light of the other evidence in this case. And you may not find [Soerings’] testimony in and of itself convincing beyond a reasonable doubt, but it's not his burden to convince you of his innocence, it's just his burden to tell the truth and let the chips fall where they may in this case, and that's what he did in this case. He told the truth, no matter how illogical it sounds, no matter how much it makes an otherwise intelligent person appear not to have common sense, he told you what happened.

And what happened was that he stayed in Washington and that Elizabeth, and probably one other person went to Loose Chippings and killed her parents.”

Prosecution Rebuttal

Updike emphasizes Söring’s late story change: “You heard him talk about this alibi now…he didn’t say anything about it in October of 1985, he didn’t say anything when he’s giving the English statements, he doesn’t know any details in December of 1985, but suddenly he gets on the stand now” and brandishes documents his lawyer had known about since 1986. The movie tickets were meaningless – unless the movie theater has got “one of those computers” there is no indication when a ticket was bought; people swing by movie theaters to buy tickets for later showings all the time. The check was cashed sometime on March 30, 1985, but there is no indication when; the defense blamed the prosecution for not doing “handwriting analysis” even though they introduced the check into evidence only at trial.

The fingerprints from Elizabeth Haysom on the vodka bottle and unidentified persons on the bottle of Old Plum brandy and the front door were irrelevant, since there was no proof they were left at the time of the crime. Updike even re-submitted the crime-scene fingerprints to check if any of them were Söring’s. Updike rejects Neaton’s claims that the prosecution would have trumpeted Söring’s fingerprints if it had found them: “if we had found Jens Soering's fingerprints on one of these bottles, not in blood, it would have meant absolutely nothing…. because then they could say, and quite truthfully, Jens Soering had been in the house before. It would have meant nothing.”

The lab tested two hairs found in the downstairs bathroom and found that one was a “Caucasian” hair and the other an animal hair. There was no need to proceed with further testing: “If it had turned out to have been Jens Soering's hair, he had been in the house before. If it had been Elizabeth Haysom's hair, she lived in the house, meant nothing. It was not in blood.“

As for the rag in the washing machine, “Oh, the rag in the washing machine, now that's a good one, too. Now that, that rag in the washing machine, ladies and gentlemen, has got blood on it, not enough that the investigators can see with the apparent eye, but they do the luminol and they see a little blood on it, it shows up, so they submit it.“ It could “very well” have been Elizabeth’s blood, but there was again no evidence it was deposited during the crime: “I mean she said that she was — it’s been admitted and acknowledged she was a drug addict, she may very well have been in the house at some other occasion and got The blood on that particular rag. But you see, you cannot [tell the] age [of] the stain -- When was it put there, that's what we want to know.”

The defense’s explanation makes no sense – why would the killer go to the effort of obscuring or eliminating all of the physical evidence, then leave a cloth with their own blood on it behind? The defense’s suggestion that a slipper found near Mrs. Haysom’s body might have been worn by a killer is refuted by the presence of bloodstains in the slipper itself: “Elizabeth shows up with somebody else there at the scene, a friend of hers, and the friend says, well Elizabeth, before we murder your parents. I’d like to get comfortable. Do you mind if I put on some bedroom slippers, do you mind if I wear Nancy's.“

Soering’s claim that he did not know Elizabeth planned to kill her parents was a lie intended to reduce his criminal liability: “Whoever was making that alibi up there was just as involved as the person who did the killing as a matter of fact, as a matter of law; Elizabeth Haysom knew that, Elizabeth Haysom pled guilty to it.” The defense’s attempts to paint her as the “star witness” were misleading: the only star witness in this case was Jens Soering. The alibi story has other flaws. Jens Soering claimed Elizabeth needed an alibi for picking up the drugs in Washington. Yet he also admitted that the plan (in his telling) was for her to deliver them to Jim Farmer in Charlottesville on Sunday, March 31, 1985. How would a (flimsy) alibi for Saturday help Elizabeth conceal a drug deal on Sunday?

Updike again stresses that the alibi was for the entire weekend of the murders, which is why Soering kept the movie tickets and restaurant bill from the Friday before the murders. This shows that the plan had been calculated in advance. The light in Elizabeth’s room was obviously switched on by one of the officers to help illuminate the scene.

The fact that the culprit turned off all the inside lights but left the outside porch light on is also revealing:

“As you step out that front door from the darkness out into the front, and you're all bloody, and that light is shining on the whole front yard, now the natural thing to do, of course, is -- well I have concealed everything else, I sure in the world would like to get to my car without that light being on. Well he had been in the house once, Elizabeth Haysom lived there, Elizabeth Haysom would have known where the light switch was.”

Turning to the sock-print: “Ricky Gardner …got Jens Soering to walk across this paper. He did it on January 30, 1990 at 5:30 p.m., Bedford County Sheriff's Department. He got him to walk across a paper for us, he got him to walk across paper for the defense attorneys. This one with the blue label on it is the one for the defense.” Updike argues that LR3 is completely consistent with Söring’s foot and reflects the way he walks, which creates a “double impact” which was also seen in the samples he was ordered to provide.

Updike ends his rebuttal with the classic prosecution argument on how the jury must view the evidence as a whole. When they jury evaluates all the evidence, they will see a sort of Venn diagram of overlapping circles: The person who committed this crime had to have Type O blood, and a foot consistent with LR3, and the opportunity to drive to Boonsboro, and knowledge of where they lived, and had to be someone the Haysoms would let in voluntarily, and had to be someone lacking a sexual or financial motive for the crime: “Who had that motive? Well you say Elizabeth Haysom did. Certainly she did, she encouraged him to kill her parents. He had it as well, we know by virtue of what he had said when he made his statements in England about how this was building up in him over a period of time, by virtue of his writings.“

Updike goes on: The culprit also had to have injured himself or herself at the crime scene; Elizabeth had no visible scars at any time, but Soering was seen with injuries by Don Harrington. Soering’s own behavior and statements also incriminate him: his flight from a brilliant future, his confessions, his letters. The circumstantial evidence progressively excludes all but a handful of people as potential perpetrators, and Soering’s own confessions are direct eyewitness evidence which seals the deal.

Updike concludes: “Ladies and gentlemen, under this evidence, he should be convicted of first degree murder, because that is the only thing this crime could be, he should be sentenced to life imprisonment on each case. Not an easy thing to do as I said, it's the just thing to do. And if you doubt, look at what was done, and remember you how he acted up there. Thank you.“

Analysis

Both lawyers delivered competent closing arguments. A good closing picks two or three themes and hammers them home – something which is hard to do in a case with as much evidence as this one. Updike’s themes were the confessions, the signs of premeditation, and the gaps and contradictions in Söring’s story. Neaton’s themes were loose ends left by an investigation driven by tunnel vision and Elizabeth Haysom’s flawed character and proven capacity for deception and manipulation.

Neaton also introduces the shadowy figure of the potential accessory, an addition to Soering lore whose importance cannot be overestimated. There is no suggestion in Jens Söring’s own testimony that Elizabeth committed the crime with someone else. When she returns to him in the Marriott at 2:00 am, she says “I killed my parents”, not “we killed my parents”. Söring even describes bloodstains on Elizabeth Haysom’s own arms. According to Söring, the pair sat together for four to five hours (from 2 am to “six-ish, seven-ish“ on the morning of 31 March 1985 while Elizabeth fed Söring detailed stage-descriptions of how she killed her own parents:

“Q: Well give the jury an example of how that conversation took place.

A: Um, for example, this business about, you know, what happened at the house, where was what was her mother doing, what did you do next, what did you talk about, what room aid you move into next, the business of moving from the living room into the dining room, what did you do then, well, you know, you had a meal, and I'd say okay, and put that into my story and repeat it back to her and try it out on her, okay?”

One might think that if Elizabeth wanted Jens to be able to recite a believable story of how the murders happened, she might have mentioned that there was someone else there the whole time helping her kill them. Perhaps this just slipped her mind. For five hours.

Soering’s account immediately raises the question of how petite Elizabeth, who at 50 kilos weighed 25 kilos (55 lbs) less than her father, managed to single-handedly subdue and murder him and her mother. Neaton came up with a solution by arguing, based on what he claimed to be discrepancies in the crime-scene evidence, that another person must have been at the crime scene. Söring must have ground his teeth in frustration that he had not thought of that himself. Yet Soering was clever enough to recognize a particularly useful smokescreen when he saw one. He lost no time in taking up the “shadowy-accomplices” argument and continues to make it to this day.

Neaton also endorses Söring’s version of events. This is not always a given. If a defendant takes the stand and spins a tale no sane person could believe, the defense attorney will often choose not to draw attention to this testimony in closing arguments. Instead, he will simply try to build a case for reasonable doubt. Neaton instead decided to endorse Söring’s version of events. This was the correct choice strategically. Söring’s story was far-fetched, but it did not require the jury to, for instance, reject the laws of gravity or believe in an evil twin. Further, it did at least attempt to defuse the main evidence against Söring.

Yet it needed all the help it could get. Neaton’s endorsement was yet another indicator of his skill as a lawyer and his commitment to his client. In other respects, Neaton’s closing was the typical catalogue of gaps, errors, and inconsistencies in the prosecution’s case. This is the kind of closing argument you might hear at any of America’s thousands of courthouses. Neaton’s presentation was somewhat disjointed, but he had his “schoolteacher board” to help keep the jury oriented.

Thirty-five years later, it is striking how many of Updike’s and Neaton’s arguments still frame perceptions of this case. Söring is still suggesting to audiences that there is something suspicious about the unknown fingerprints on the Old Plum bottle and Elizabeth’s fingerprints on the vodka bottle, for instance. Through the decades, at least six men – Jim F., Ned B., the guy from the Tony Buchanan story, “some guy/guys Elizabeth knew from the drug scene”, and William Shifflett and Robert Albright – have been drafted (unwillingly) into the role of the shadowy “accomplices”.

When people begin reading these old trial transcripts today, they are often surprised to find that most of the arguments Söring is making today were already the subject of vigorous debate in 1990. Söring presents his arguments about the sock print or judicial bias or Elizabeth’s credibility as if they are open questions. This leads his more gullible supporters to ask an obvious question: “What kind of legal system would not bother to answer these basic questions before sentencing someone to life in prison?” As we will see, famous German television host Markus Lanz practically leaped out of his chair after hearing Söring’s litany of complaints and asked rhetorically why “nobody stood up and said ‘stop’!”. A German judge even confidently pronounced that America was not governed by the rule of law.

What these foolish men – and so many others – have in common is that they never bothered to find out what actually happened at Söring’s trial. The issues Söring raises were not ignored by a callous system which couldn’t care less about the truth. They were instead subjected to vigorous public debate among three experienced lawyers – Richard Neaton, Jim Updike, and William Cleaveland – not just before the jury, but before a television audience.

Söring’s capable team of lawyers was given the chance to cross-examine every prosecution witness and often did so for hours. The defense was permitted to introduce its own evidence directly attacking the prosecution’s claims. The jury heard the closing arguments from the prosecution and an equally vigorous presentation by the defense. Söring’s trial lawyers did an outstanding job defending an extremely difficult case – any case where the defendant has given two admissible confessions to police is per se a difficult case – but, as Richard Neaton later commented, they weren’t magicians.

The jury found Soering guilty not because it was bamboozled or hypnotized, but because the prosecution’s theory had been proven beyond a reasonable doubt after an eminently fair trial. Söring has spent the last 35 years attacking this verdict, the turning point in his life, by means both fair and foul. He will surely do so until his last breath. But the verdict has survived, because it is built on that most solid of foundations: the truth.

After the Spring semster of 1985, Jens Söring visited his parents in Detroit, Michigan. Apparently the fact that the parents of Söring’s girlfriend had just been brutally murdered just weeks ago just sort of never came up. To be fair, the Detroit Tigers were having a pretty good season in 1985 (they’d end up in third place), so that may have dominated the conversation.

Jetzt verdienen Sie also Geld mit dem Tod zweier Menschen? Das, was sie Söring etliche Male vorgeworfen haben?

So langsam frage ich mich, wie tief die Zusammenarbeit zwischen Ihnen und den Haysoms ist? Was sind ihre Absichten mit dieser Kampagne? Sammeln Sie finanzielle Mittel um Sheena Haysom Mund tot zu machen? Oder warum kommt der Spendenaufruf erst jetzt?

College boy is pussy-whipped and commits murder.

Oh well!