The Netflix Interview and the "Second Bloody Shoeprint" that Wasn't

More warmed-over speculation in Söring's interview with Chip Harding.

Söring just posted a 22-minute interview with Söring Team 1.0 member former Albemarle Sheriff Chip Harding. In this video, as in many previous ones, Söring complains about how many items Netflix left out of its 4-part series on Söring’s case. They never mentioned the Luminol! The “second bloody shoeprint”! McClintock’s Report!

The Netflix Interview

Indeed they did not mention these things (or simply referred to them glancingly), and I’m one of the reasons. I was hesitant to give Netflix an interview because I think many true-crime documentaries are grossly misleading (and have made this case in writing in public), and suspected the Netflix series would be basically an updated version of “Killing for Love”.

So I politely declined to give Netflix an interview unless they promised to air a debate on the case between myself and John Grisham (or any other Söring supporter, including Söring himself) at least as an online bonus special. That way at least there would be one talking head allowed to set out the case against Söring for an extended period. I offered to fly to Virginia at my own expense and debate Grisham — or any other Team Söring member, or all of them at once — in any venue and any format of their choosing. I offered to share my entire trove of documents about the case with Grisham, so he could inspect first-hand some of the documents and pieces of evidence Söring scrupulously avoids mentioning to his supporters unless directly asked.

Alas, Grisham and all of Söring’s other supporters, including Söring, have uniformly rejected all of my offers to debate anytime, anywhere, in German or English. Netflix told me there simply was no way to arrange a debate, but they insisted they were eager to interview people who did not accept Söring’s innocence claims and intended to make a balanced show based on the evidence.

Eventually, they convinced me, but it took several months. We met in Spring 2022 in a rented villa in Velbert, Germany. The directors were already well-advanced with their research and had dozens of questions and follow-ups. They raised everything — the FBI profile, the Luminol, hair on the bathroom sink, the DNA, who created the alibi, the sockprint, the June 1986 confessions, Elizabeth, etc. The conversation lasted some 7 hours. I’m only onscreen for a few minutes in the fourth episode, but that’s showbiz for you.

Over and over, I repeated the mantra drilled into the head of every lawyer from Day 1 of law school: In evaluating evidence to support a conviction or finding of liability, you must review all the evidence in context: “Once a defendant has been found guilty of the crime charged, the factfinder’s role as weigher of the evidence is preserved through a legal conclusion that, upon judicial review, all of the evidence is to be considered in the light most favorable to the prosecution.” (Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307, 319 (1979) (emphasis in original).

Becoming obsessed by isolated pieces of evidence while missing the big picture is a constant threat for lawyers, detectives, directors, conspiracy theorists and true-crime buffs. Even experienced investigators or lawyers can find themselves missing the forest for the trees, and there is no better example of that than the Söring case.

Thus, whenever the directors asked me about a specific piece of evidence, I kept repeating some version of the following:

“OK, let’s pretend the bloody sockprint never even existed. What difference would that make to the ultimate, final question? None. You would still have by far the most important evidence — 5 hours of taped confessions by Söring himself. Those confessions alone get you 95% of the way to conviction. Add to that Elizabeth’s testimony, the refusal to provide samples, the flight from the USA, the statements in the letters and diaries, the Type O blood, and Söring’s own changing stories, which are also direct evidence of his guilt. All of this evidence, in context, gets you not only to the finishing line for a sound conviction, it allows you to run 20 more victory laps. All without any bloody sockprint. This is not a complex case. This is a straightforward murder case solved by a corroborated confession. That is why the appeals courts called the evidence ‘overwhelming’.”

I can’t speak for the Netflix directors, but I think I may have had at least some influence on their editorial decisions. With me, the directors raised every one of the issues that Chuck Reid, Stan Lapekas, Thomas McClintock, Chip Harding, and others have allowed themselves to become distracted by. I explained why the Luminol results on the car were meaningless. I explained why the DNA was meaningless (that quote appeared in the series!) in that it didn’t point to the existence of two perpetrators. I explained why the shoeprint was meaningless. I explained why the cigarette butts and the vodka bottle and the hair in the bathroom and the movie tickets were meaningless.

They were meaningless not just because they didn’t point toward anyone else being at the crime scene on the night of the murders, but because they were like grains of sand dwarfed by the Everest of admissible evidence showing “overwhelming” proof of Söring’s guilt. All the cherry-picking, red herrings, and isolated demands for rigor can’t change that basic fact.

I also explained that as a former criminal defense lawyer, I could say with 100% certainty that Neaton and Cleaveland must have consulted their own expert on the bloody sockprint. The result was that their own expert privately told them that yes, the sockprint was consistent with Söring’s foot. Which is why they buried the opinion and did not call their own expert at trial.

Any even minimally conscientious defense lawyer would have gotten a second opinion on the sockprint, and Neaton and Cleaveland were very conscientious and surely did so, with disappointing results. Netflix then consulted an independent forensic podiatrist, Dr. Sarah Reel, who indeed confirmed the sockprint was consistent with Söring’s foot. The same opinion Neaton and Cleaveland had heard in 1990.

Netflix certainly didn’t just accept everything I said, and the directors made their own independent decisions about what to put in the series, which is why they landed on a theory which I personally find unconvincing. But I think I helped them refocus on the big picture of the case. I also told them to never take anything Söring says about his case at face value. Treat everything he says as false or misleading until you find independent evidence confirming it. They seem to have concluded this on their own, since the theory they embraced demonstrates they knew Söring was lying to them during his interview.

There is no “Second Bloody Shoeprint”

Now to the second theme of the post, the supposed “second bloody shoeprint” Richard Hudson found at the crime scene. I still have no idea what the significance of this is supposed to be, and I suspect many of you are in the same boat. Let’s clear this up once and for all.

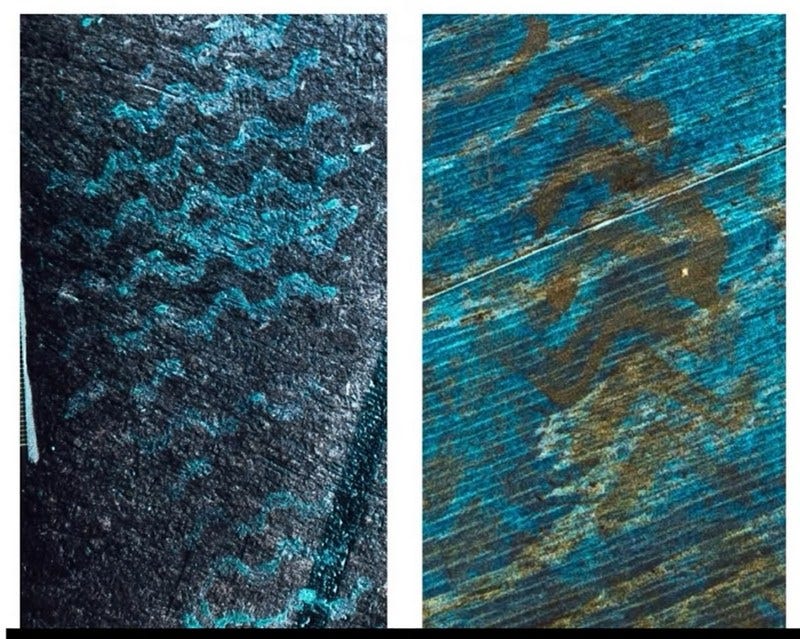

Here is the comparison of the two “bloody shoeprints” Söring shows in his own video (it’s also in the Chuck Reid report):

These pictures have been manipulated in some way; the bluish stain is not in the originals, which you’ll see below.

Interestingly, the photo on the right seems to have gone through some further transformation. This is the version Siegfried Stang reprinted in his excellent 2022 German-language book on the case, Nebelkerzen (“Smokescreens”).

Stang was intrigued, but he noticed that the photo appeared to have been altered in some way. As he recounts in his book (Kindle page 681), Stang emailed Söring on 15 January 2022 asking if Söring had the original photo. Söring replied two days later that he did not. Stang decided not to try to contact Hudson, since “all my attempts to contact people connected to the case had failed”.

Regardless of how these photos came to be, you can see there’s something wrong. The shoe print to the left in the dark comparison photo above is indeed made in blood, as you can see below in the original photos. In the supposed “second bloody shoe print” to the right, the ridged chevron patterns are not made in blood; in fact they appear to be the only non-bloody areas inside a pool of blood.

If blue symbolizes blood, as in the left photograph, then why is there no blood from the shoe tracks in the right photograph? The laws of physics say that the raised surfaces on the bottom of a shoe will be the first places to become bloody when someone steps in blood, and the first places to deposit blood if that shoe later encounters a clean surface. Were the laws of physics suspended when “suspect no. 2” was wandering around the Haysom home?

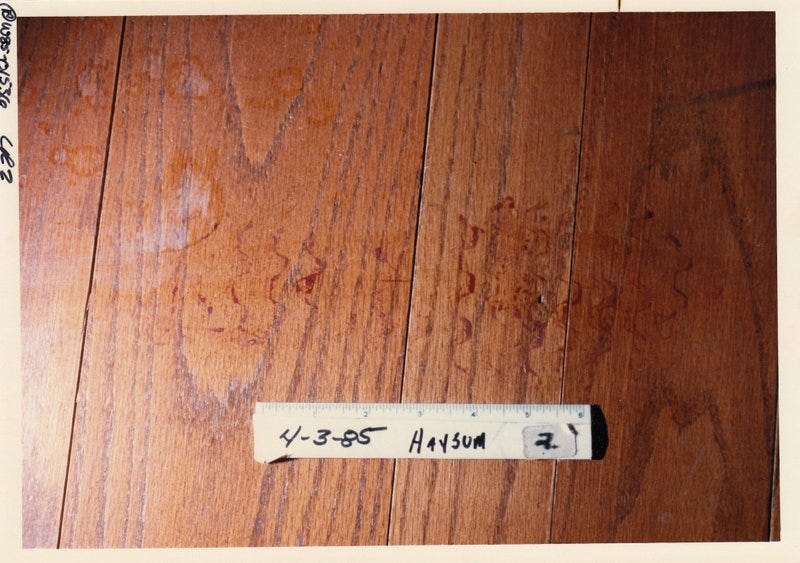

In any case, the original photos clear everything up. Here are the two partial bloody shoeprints found at the crime scene, the top one from the dining room, the bottom one from the living room:

As you can see, these prints are consistent. At trial, a shoe store employee testified that they were consistent with the pattern on Vans shoes, a type of canvas sneaker popular among skateboarders. However, both prints were too fragmentary to allow any conclusion about the specific brand, model, or size of the shoe.

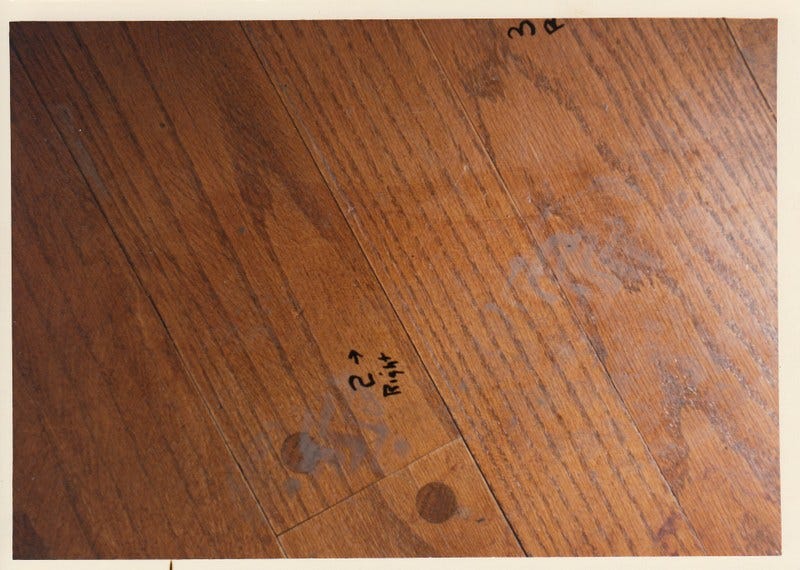

Here is the original photograph (from an area near the bar in the living room) in which Richard Hudson discerned an alleged “second bloody shoeprint”:

This is (a scan of) the original photo Söring claimed not to possess when Stang asked him. The grey smudges in the right 1/3 of the photo are the supposed “second bloody shoeprint”. Hudson has rotated it a little over 90 degrees, cropped it, and done some sort of increase-contrast operation. There does seem to be a slight dark smear under the markings which could be from a partially-cleaned bloodstain.

You’ll notice, of course, that the “shoe print” itself is …not made in blood. Since the faint gray chevron patterns in the photo above were not bloody, they could have been deposited at any time before or after the blood smear. Assuming they are in fact a shoe print, it could have been deposited by anyone: A detective, a coroner’s-office employee, a crime-scene tech, one of the Haysoms themselves, their daughter who visited them one week before the killings, a houseguest, a plumber, a yard worker, Annie Massie, or dozens of other people.

I’m not going to accuse Chip Harding or Richard Hudson of any wrongdoing here. Always default in favor of incompetence unless there is direct evidence of malice. But I have no idea how they convinced themselves there was a “second bloody shoeprint” left on the night of the murders. As we see, there is no basis for that claim. I can only conclude they were mislead by confirmation bias and eagerness to help a (supposedly) innocent man fight a (supposedly) unjust conviction. Tragically, they were wasting their time all along.

Lieber Andrew, wie sieht es gegenwärtig mit der deutschen Ausgabe Deines Buches aus?

Ist ein Erscheinungstermin in Sicht?

So Chuck Reid 3 video is out.

More supposition, theorising and trashing of peoples' reputations.

Although Terry Wright cracked the case, he never actually worked the investigation!

Kim, Harrington and let's not rule out Julian Haysom!

But let's pin this squarely on Farmer who was apparently caught years later with all sorts of drugs and scales and whose birthday it was on the night of the murder and whom Elizabeth must have gone to see in the rental car and then they

switched cars which is why no blood was ever found.

Soering has finally come clean and admitted the story about getting lost for 200 miles was not true!

And he skipped the country before providing fingerprints and a blood sample because he didn't want to be separated from Elizabeth!

So why didn't he accompany her to Jim Farmer's birthday party?