Chapter 2 of "Martyr or Murderer": The Christmas Letter

This letter, as fascinating as it is disturbing, reveals Jens' growing obsession with Elizabeth.

Hi! Chapter 2 of my new book is below all the bla-bla-bla. Trust me, it’s interesting. The book chapter, not the intro.

Intro

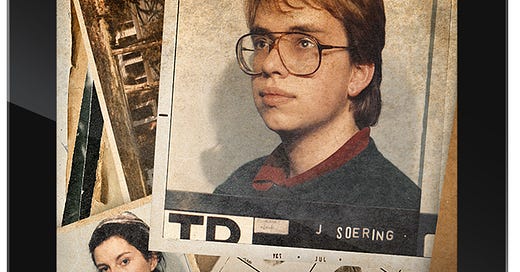

I’ve been busy lately, including planning interviews. But now I thought I’d share a chapter of my new book, Martyr or Murderer? Jens Soering, the Media, and the Truth. You can get it anywhere on Amazon, and can get a paper book if you want! German readers: I hear you! I am working on a German translation, which I hope to release in mid-2023.

For now, though, I wanted to share Chapter 2 of Martyr or Murderer, which deals with the infamous long letter which Jens Söring composer over Christmas 1984, but never sent. Here’s the chapter:

Martyr or Murderer? Jens Soering, the Media, and the Truth, Chapter 2: “The Christmas Letter”:

Over the 1984-85 Christmas holidays, the pair were forced to split up, which Jens described to psychiatrist John Hamilton in 1986 as “mental torture”. Jens flew to Detroit, where his father was now stationed, to spend the holidays with his family. Elizabeth spent a few days in Lynchburg with her parents, then departed for a ski vacation in Yugoslavia organized by her mother. The couple decided to cope with their enforced absence by indulging their mutual passion: writing. The result was one of the strangest pieces of evidence ever presented to an American criminal jury: the rambling, obscene, impassioned, surreal, often-sinister musings of two intellectually precocious and disturbed teenage lovers.

Both letters are actually more like diaries: Instead of sending off letters when they were written, both Elizabeth and Jens decided to keep adding to an initial letter with new dated installments. Elizabeth actually sent some of her letters, while Jens decided to simply preserve his own diary/letter (some 40 pages long) and present it to Elizabeth after they reunited in Charlottesville in January 1985. The couple were also in touch by telephone during much of this time. The letters, therefore, were more of a way to record general musings (especially about their budding love), rather than a way to keep one another current.

Before we consider the letters in detail, two questions deserve attention: How did they survive, and why were they entered into evidence at both Elizabeth and Jens’s trials? The question of how is easily answered but surprising: Jens kept copies of letters he received from Elizabeth Haysom, and of letters which he sent her. That may not seem too extraordinary at first, since Soering had vague visions of a creative career, and had clearly put hours of effort at the typewriter into these missives.

Jens, however, went much farther than merely keeping copies of the letters. When he fled the United States on October 13, 1985, he took along an entire suitcase filled with the correspondence between himself and Elizabeth, along with various notes, sketches, magazines (including “Soldier of Fortune”), writings, receipts, and other items. He had stuffed this archive into a suitcase which he lugged around Western Europe, Yugoslavia, the Eastern Bloc, Thailand, and England. The suitcase was in the couple’s shared apartment when they were arrested in London in March 1986. To this day, Soering cannot explain what drove him to drag a suitcase full of incriminating evidence around the world and give the police consent for the search which would ultimately reveal the trove. When asked to describe the decision to keep this mobile archive during his 1990 trial, he attributed it to his being a “hoarder”. He now describes keeping the documents as one of the worst mistakes of his life. As we will see, there’s competition for that title.

As to why the letters were introduced at trial, the answer is simple: They contain veiled hints of violence being done to Derek and Nancy Haysom, set down four months before their murders. And it wasn’t just Jens engaging in these gruesome speculations. During her 1987 trial as an accessory before the fact to murder, prosecutor Jim Updike forced Elizabeth Haysom to read excerpts of her own letters to Soering in which she stated that she “despised” her parents and wrote: “My mother begins her 6th gin, I pray she’ll use the poker on my cold, goading father.” Later she wrote: “Why don’t my parents just lie down and die? I despise them so much.” She mentioned eliminating them by “voodoo”, a theme which Jens Soering would take up: “Would it be possible to hypnotize, voodoo them, to will them to death. It seems my concentration on their death is causing problems. My father nearly drove over a cliff at lunch … my mother (drunk) fell into the fire. I think I shall seriously take up black magic.” This passage was especially damning: “My parents are going mad. We can either wait until we graduate and then leave them behind or we can get rid of them soon. My mother said today that if some accident befell them she knew I would become a worthless adventurer; more maternal acumen.”

Updike, as we will see, portrayed Elizabeth Haysom as a supremely ungrateful daughter, given that these churlish digs were aimed at the people who had financed the very vacation she was enjoying as she insulted them. Elizabeth Haysom agreed, calling these sentiments “disgusting [and] atrocious”. After being forced to read long excerpts from her letters to Jens during her cross examination by District Attorney Jim Updike, Elizabeth admitted:

A: I’m afraid, sir, that it was a fantasy of mine for many years that my parents would die.

Q: You fantasized their death for many years.

A: I fantasized that they would be out of my life.

Q: By death?

A: It didn’t matter how.

During her 1987 trial, when she was attempting to mitigate her guilt, Elizabeth vacillated between frank acknowledgements like the above and protestations that the remarks about her parents were mere fantasies, and that she did not want to see them killed. At the end of the day, though, these passages show entitlement, ingratitude, and callousness. More important, however, was their effect on Jens Soering. Reading these passages, Soering might have imagined, and in fact did conclude, that Elizabeth Haysom would not only not be particularly disturbed if her parents were eliminated, but might well be relieved and even grateful toward whomever made it happen.

Yet it was Jens Soering’s series of letters to Elizabeth which turned out to be more legally relevant. Elizabeth Haysom, as we will see, conceded her guilt and admitted the passages in the letters meant what they said and were “atrocious”. Jens Soering, on the other hand, claimed that his letters were innocuous, and protested his innocence of the crime at his 1990 trial. Yet Soering’s letters, thus, not only shone a light on his deeply disturbed personality (as did Haysom’s on hers), but also contained admissible proof of his intent to harm the Haysoms.

Söring’s compendium of letters is usually known as the “Christmas Letter” or the “Diary Letter” because of its diary-like, date-by-date structure. Scotland Yard detective Terry Wright has a more colorful moniker based on its macabre contents: the “Psycho Letter”. Before we get to the incriminating portions, it’s worth conveying a sense of how bizarre and revealing this document is. It consists of about 40 pages (depending on which version one consults), most of which are typewritten using a standard typewriter. The pages are festooned with handwritten insertions, deletions, and notes and diagrams. This is how the letter begins:

Dec. 27, 1984 (almost 10 p.m., listening to Sweet Emma’s Preservation Hall Jazz Band from New Orleans -- I wonder how your roomie is doing and whether mine will be there to disturb us after I arrive on Jan. 14 at 4:35 p.m. in C-ville.)

I love you; Je t’aime; Ich liebe Dich. Which, incidentally, is why I despise telephones. I have to (and am) grateful that I can listen to ELIZABETH!!! (and other forms of typographical accentuation -- oh shit, I’m slipping between languages again. Never mind. Where was I? Oh yea. To continue where I left off..)) jabbering away happily and at the same time Ma Bell [a nickname for the American telephone monopoly] in her ugly- American, 3-D, fiber-optic, techni-color, computer-controlled and hypho-nated apron is standing behind me, covering the fat and flab with the ever-popular just-above-the-knee-length bermuda shorts, the glitter-frame sunglasses and, to top it all off (what a pun), pins thru her head (to revive the flagging spirits by means of acupuncture), beating me over the head with a sign that says BUT SHE AIN’T HERE, BUB.

I ramble.

More than usual.

Shall control said rambling thru telegram style discourse.

Love you.

Miss you.

The letter meanders along this stream of consciousness, invoking references to “the first Japanese-Jewish Matell action figure ... the only major piece of art to be banned on every continent except New Guinea”, “Ryuishi” Sakamoto, and “Jeremy Fitzgerald Rubehardt, the highly talented but practically unknown co-star of the Irish production of The Circle’s Corner, or Does Lady Di Wear Naughty Underwear?”.

As if this introduction weren’t enough, Soering explains his method:

The object? Write a 20,000 word sentence.

Elizabeth, meet my letter. Or rather, the style in which I write letters. Nothing in my head. Just a mechanical snail, as predetermined (or not) as anything else in this bowl of spaghetti we meatballs (or are we just the spices in the meatballs? How profound!!!) call a universe… OK, have you heard the one about the dead baby with three heads? Well, let me tell you. Anyway, a mechanical, predetermined (or not) snail, crawling along the paper, leaving a trail of black slime which you, silly thing, think means something. Arf arf.

The letters aren’t all word-salad. Soering’s train of thought sometimes coheres for a few paragraphs (such as when he discusses his family or his reaction to Saul Bellow’s “Humboldt’s Gift”), before again shattering into a kaleidoscope of thought-shards. Expressions of unbounded, self-hating, submissive devotion recur throughout:

· “The most incredible person in the world loving you with every bone in her body or pretending so well it doesn’t make a difference…”;

· “I’ve even got Elizabeth believing I’m worth while, but I’m not, because I can show nothing! I’m even fucked up inside, and really fucked up, too. Look at this I’m writing — I’m a fucking schizo!”

· “After a while she’ll realize the pile of fake shit I am and leave me in an even worse mess and I might hurt her, too. Emotionally, you know.”

· After calling Woody Allen “that boring little Jew (does it please you that I let my almost nonexistent anti-Semitism out just to please you?)”

· “I know that I am harping much too much on the “Oh, me, Oh, my, she’s a-gonna leave me” thing. I got your letter on the 3rd [of January], and I was getting paranoid. I am still, but much less so. Look, I will really try to keep it under control, o.k.? I could have edited all that shit out, but somehow I wanted to leave this complete. I love you.”

Soering even invented an acronym for his mental state: “I am in the moment engaged in Self-Reflexive Analysis and Perpetuation of Neurosis (from now on to be known simply as SRAPON).” As we will see, these expressions of neurotic possessiveness, which echo the comments of classmates about Soering’s clinginess and jealousy, were on motive for the killings.

Yet Soering also tried to impress Haysom with his erudition and wit, something he knew she valued. Soering thus also discusses the structure of the galaxy, St. Anselm’s spirituality, The Waltons, Hitler, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the color used to paint bombers, “ideology bombs” which can somehow force changes in mass opinion, bonsai trees, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Alan Watts, Sophie’s Choice, pheromones, John Cougar Mellencamp, Bernhard Goetz, Charles Bronson, The Red Pavilion, The Tao of Pooh, “absurdism/existentialism”, and countless other pieces of culture high and low which would have occupied the mind of a bookish, politically-aware teenager in the mid-1980s.

Soering also discusses his own aspirations: he wants to avoid the fate of an office drone and instead create epoch-making art (“You know, if architecture could support me, I’d do that, but the job situation there will remain rather hopeless.”). The subject of money comes up repeatedly. Soering has, by all accounts, always been concerned about money. He mentions it repeatedly in the Christmas Letter, spoke of it frequently with Elizabeth Haysom (she noted at her trial that “Jens was very concerned about money”). In the Christmas Letter, Söring writes:

I worry about money a lot… I need to find a way to earn cash in a way that pleases me and doesn’t take up much time, I can just see myself joining the foreign service -- nice lifestyle, easy hours, completely frustrating and certain to turn you into the kind of schmuck my father is. Argh!

Söring returns to the subject of his father in a later portion of the letter:

The last ties to my father are broken. He is worse than he used to be and he is losing his last redeeming quality, his precision in technical matters. He knows nothing about me, we have nothing to talk about, he trusts noone, is loved by noone, yet thinks he is loved... he actually thinks his wife and younger son love him, the poor fool (he’s finally realized he has no relationship with me but - still thinks we had one. He did not, not for ages.). I pity him immensely, he has nothing, and you know what? A part of him knows it. He will die soon. It’s on his face. He looks about ready to have a heart attack.

Söring then refers to his mother as a “suicidal drunkard” who is just waiting for her own mother to die so she can inherit “around a million”. As for his maternal grandmother, Söring denounces her as a “poor, lonely, wicked person” who is “wilfully wast[ing] her fortune”. Again, Söring’s concern for money comes to the fore. Indeed, it would be a dispute between Söring and his family over his grandmother’s estate which would lead to Söring’s final rupture with his family in 2001.

The letter also contains three references to Söring’s own “excessively bizarre sexual fantasies” which might have been “caused by…one thirteen year old girl striking me once quite viciously with her riding crop from atop a horse in a German summer camp when I was about to turn ten”. But the passages which would haunt him later were the veiled fantasies of violence, including towards Elizabeth Haysom’s parents. On Page 6, Soering writes this dialogue with himself:

(Tell Elizabeth; I don’t want her further involved with this.)

Yeah, neither do I. It’s going to hurt a hell of a lot, though.

(Especially if she doesn’t take a hint and continues to hang around a psycho like you…)

Yeah. For her and me.

(You know, that certain “instrument” for a certain “operation” on somebody’s relatives?)

Yeah…

(Use it on yourself.)

Maybe.

On page eight, Söring returns to the theme: “By the way, were I to meet your parents, I have the ultimate ‘weapon.’ Strange things are happening within me. I’m turning more and more into a Christ-figure (a small imitation, anyway), I think. I believe I would either make them completely lose their wits, get heart-attacks, or they would become lovers (in an agape [i.e., chaste Christian love of mankind] kind of way) of the rest of the world.” On page 10, he mentions a “dinner scene”: “…love is a form of meditation. And the ultimate ‘weapon’ ‘against’ your parents. My God, how I’ve got the dinner scene planned out.” A few pages later, he returns to the theme: “Depending on his mental and emotional flexibility, your father, for example, could quite well die from a confrontation with [Soering’s spiritual insights], if he is too entrenched in hate and/or SRAPON (same thing in many cases), or he could do something silly like trying to give me all his dough. I’m not overestimating, I think.”

On page twelve, the subject of property comes up again in another odd passage: “I can see myself depriving people of their property quite easily – your dad, for instance. Even more easily can I see myself depriving many souls (if they exist) of their physical bodies (which might not exist, either) in the course of fulfilling my many, many excessively bizarre sexual fantasies…” Yet these are not the most explicitly threatening passages of the letter. On page 19, Soering addresses the fantasies in Elizabeth’s letter that her parents could be got rid of: “To your actual letter: the fact that there have been many burglaries in the area opens the possibility for another one with the same general circumstances, only this time the unfortunate owners…” On page 29, he writes:

I’ve felt this, I’m feeling it now inside me, this need to plant one’s foot in somebody’s face, to always crush (thank you, Orwell, for that metaphor you borrowed)… I have not yet explored the side of me that wishes to crush to any real extent – I have yet to kill, possibly the ultimate act of crushing, with the possible exception of sex, which, all of Freud’s detractors to the contrary, I feel is somehow centrally connected with this death side…

When Soering testified at his June 1990 trial, he was forced to read all these passages aloud to the jury.

Soering delivered his mammoth diary-letter to Elizabeth after both were reunited in Virginia in mid-January 1985. She recalled:

So the first time I ever saw it was sometime in January. I read the first few pages and we [i.e., her and Jens] agreed to the fact that it’s a very tense and boring document. I read it, I don’t remember how many pages, read a certain number of them and gave it back to him as he asked, as he asked for many other letters, and he comments on those… it was very difficult reading and very boring, very dull and very strange.

The letters Jens and Elizabeth exchanged over Christmas foreshadow the events of 1985, which culminated in Jens and Elizabeth’s hasty flight from the country in October of that year. As an initial matter, they show Elizabeth’s intense, conflicting emotions toward her own parents. Although she acknowledged her own privileged upbringing, she regarded her parents as remote, status-obsessed, even dictatorial, and speculated that they would use her financial dependence on them to control her, possibly for decades. She had also suggested to Jens that she stood to inherit a large sum if they died, although this was an exaggeration (the total estate has been estimated at just under $1 million, and would be split many ways). Later, Elizabeth admitted manipulating Soering into sharing her contempt for her own parents, although she denied specifically trying to induce him to murder them.

Soering’s actions and letters reveal obsessive love, a jejune conception of sexuality and relationships, and a crushing inferiority complex. He obviously spent most of his Christmas vacation obsessing on Elizabeth and her attitude towards him, and gave free rein to his emotions in the letter, even as he worried that he might drive her away precisely because of his clinginess and insecurity. Soering was also very “worried” about money, and fantasized about finding some line of work which would not require much effort. Soering’s attitude toward his own family was just as ambivalent and scornful as Haysoms, if not more so.

Both letters evince a phenomenon probably as old as families themselves: The tendency of precocious teenagers to regard their parents as “schmucks” who had wasted their lives in thrall to boring jobs and suburban tedium. Yet Söring’s letters go a good deal further, with their references to his mother as a “suicidal drunkard”, their grandmother as a “poor, lonely, wicked person”, and their father as a “poor fool”, loved by nobody, whose impending death from a heart attack Söring predicts with icy aplomb.

It would be going too far to say this letter shows Söring was capable of murder, but it shows a startling degree of callousness. The fact that Söring preserved these letters is equally revealing. Soering thought of himself as a young man destined for greatness of some sort, and hoarded his own writings and documents about his life in preparation for the whatever fame which he felt awaited him. As we will later see, Söring was already thinking of marketing his life story in June of 1986, when he was a confessed killer.

Finally, the letters reveal that Jens Soering was already entertaining fantasies of some sort relating to Elizabeth Haysom’s parents. At his trial, Söring explained the references to “crushing” and the “dinner scene” as a reference to using some form of spiritual energy – hypnosis, voodoo, or Christian love (“agape”) – to transform their attitude towards Jens and Elizabeth’s relationship. Yet this innocent reading is undermined by Söring’s sinister reference to a “burglary gone wrong”.

When confronted with this passage at his 1990 trial, Soering, who knew he would be confronted with it and had had four years to prepare, first deployed a rhetorical trick, pointing out that “there was no burglary staged at the crime scene”. Prosecutor Jim Updike, exasperated, pointed out that this was obviously not the point. Söring then resorted to his second line of defense: All of the references to crushing and death and the “dinner scene” burglaries were mere “fantasies” concocted in response to Elizabeth’s equally lurid speculations. Yet the Haysoms ended up dead less than four months after Soering committed these phrases to paper.

Although I understand English quite well, I'm waiting for the German edition of your book.

But you don´t need to be in a hurry. I am patient.

I enjoy reading the book although I am already pretty well informed about the details. It’s nice to read things in sequence.