Chapter 13 of "Murder or Martyr? Jens Soering, the Media, and the Truth"

Jens Söring's testimony in June 1990, including the cross-examination. Soon to come in German!

Hello everyone! This is a draft of Chapter 13 of my book on the Jens Soering case, which you can buy here on German Amazon, and here on English-language Amazon.

Deutsche Leser: Deutsche Fassung kommt Mitte Dezember!

Chapter 13: Söring Takes the Stand

Part I of this book dealt with the first phase of the Söring saga. During this phase, nobody, including Jens Söring, denied he killed Derek and Nancy Haysom. Documentary sources about Jens Söring’s state of mind and legal strategy from 1986 to 1990 are rare, since the extradition fight came before the era of the Internet and, in any case, did not revolve around Söring’s guilt or innocence. There is no evidence Söring ever claimed to be innocent of the crime before June 1990. Söring claimed in a 2007 television interview that he told his family “the truth” – that is, that he actually had not killed the Haysoms – beginning sometime shortly after his arrest. However, Söring’s family members, who supported him generously during this time, remained tight-lipped toward the media, a policy they follow to this day. None has ever confirmed that Söring claimed innocence before June 1990.

Nor have any of Söring’s American, British, or German lawyers ever commented on what he told them between June 1986 and June 1990. They are, of course, bound by attorney-client confidentiality. Söring could waive this protection, but has never done so. We thus have no evidence that Jens Söring ever claimed to be factually innocent of killing Derek and Nancy Haysom before 18 June 1990, when he took the stand for the first time to tell his new story. This watershed event began Phase II of Jens Söring’s story. From this point onward, Söring constructed an elaborate alternate history of his relationship with Elizabeth Haysom and his involvement in the murders of her parents. Just as importantly, he fought to convince the world that this new story was, in fact, true. His first attempt to do so took place on June 18, 1990, when he took the witness stand to testify in his own defense.

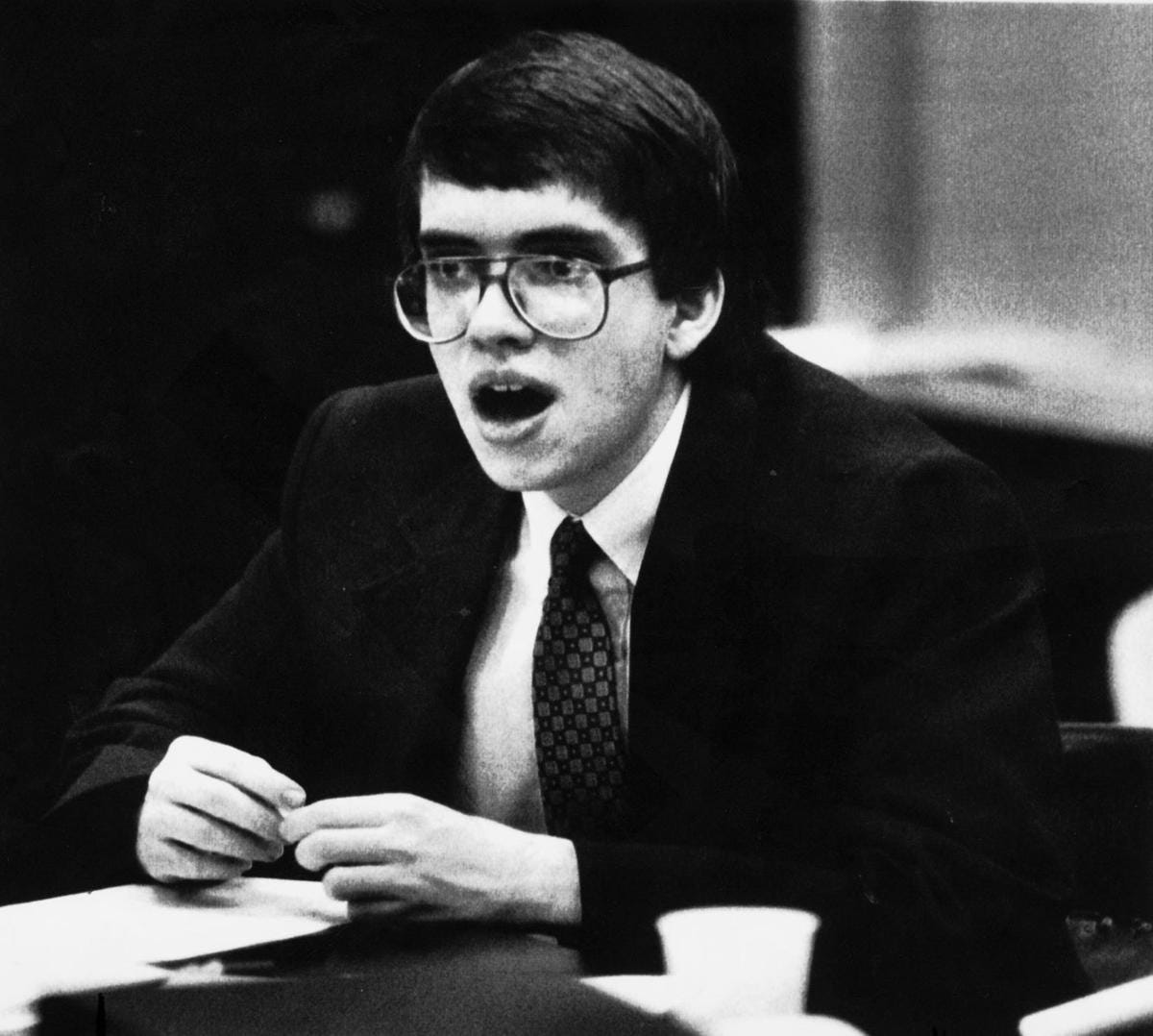

As a witness in his own defense, Söring enjoyed advantages and disadvantages, many of which were two sides of the same coin. His first advantage was his earnest, bookish appearance. Söring did not look like a killer. Detectives and lawyers know that appearances are deceiving, but thousands of laypersons have concluded that Söring must be innocent based on his nerdy appearance. Further, Söring had no criminal record and no history of serious violence, aside from fighting his roommates after getting blind drunk to forget a girl. Another advantage was Söring’s intelligence and articulateness. He speaks in full sentences, even full paragraphs, and has a large vocabulary.

This advantage, however, would prove double-edged. As we’ve seen from his interviews, Söring often rambles on, volunteering more information than needed to answer a question. Further, Söring can come across as condescending know-it-all, delivering mini-lectures to show off his knowledge. Finally, as his letters show, Söring has an uncivil tongue. He harps on the personal faults of people he dislikes (and even people he likes), invoking stereotypes about clever Jews, frustrated housewives, femmes fatales, mindless office drones, or lovelorn closeted lesbians. In one of his letters to Elizabeth, he tried to bolster her spirits by claiming that the “yokels” (i.e., ignorant country folk) of Bedford County would be no match for the powerful network of insiders and prominent officials he had assembled to support him (which did not exist). As we’ll see, Jim Updike seized on this passage during his withering cross-examination of Söring.

The first part of Söring’s testimony was the “direct examination” by Richard Neaton. Direct examination is a nonconfrontational discussion in which a lawyer helps his client tell his story to the jury. At the very beginning, Neaton asks Söring whether he killed the Haysoms or was present when they were killed, which Söring denies. Neaton then moves on to 30 March 1985. Söring says he and Elizabeth woke late, then went strolling and shopping in the prosperous Georgetown area of Washington. The had a late lunch, sometime between 3:30 and 4:00 p.m. At no point did anyone mention killing the Haysoms.

However, Elizabeth confessed she had begun using “drugs” again, which “surprised and worried” Jens. She was in debt to her drug dealer, a fellow UVA Echols scholar named “Jim Farmer”. When Söring mentioned this name, whispers went through the courtroom. Many in the courtroom knew who Söring was talking about, and could hardly believe Söring was accusing him of being a drug dealer. One courtroom observer posted the following on my blog:

Jim Farmer’s father is the Honorable James…Farmer. He was for many years the judge of the General District Court of Bedford County. That court is in the same building as the circuit court [where Söring was being tried]. I regarded this statement by Jens as an attack on the court itself. I felt very tense hearing that, and I knew that many people in the courtroom that day knew exactly who Jim Farmer was. And I knew it was a very cold, calculated libel by a desperate young man.

As we will see, this “cold, calculated libel” would eventually take on a life of its own, resulting in a 2016 documentary film which insinuated – two years after his death – that Farmer was not just a drug dealer, but might even have played a role in the murder of the Haysoms.

Elizabeth, Söring claimed, said the only way she could pay off her debt to Farmer was to meet him in Washington, D.C., pick up a load of “drugs”, and carry them back to Charlottesville the next day, Sunday, 31 March 1985, when Jens and Haysom would return to UVA. Söring couldn’t accompany her to pick up the drugs, because Farmer (or his associate) didn’t want anyone else knowing about the plot. Elizabeth said she was concerned that after she had ferried drugs for Farmer, he would be able to blackmail her, since Jim Farmer’s parents lived in Lynchburg and knew the Haysoms.

Farmer could then coerce Elizabeth into more drug runs by threatening to tell Elizabeth’s parents that she had run drugs for him, and even naming the specific time and place this had occurred. Therefore, the only way Jens could help out was to “basically function as an alibi” by staying in Washington D.C., and buying double movie tickets and room service. That way, if Elizabeth were ever accused of doing a drug run, Jens could not only claim he had been with her the whole afternoon, but even prove it with documentary evidence.

Elizabeth went off to meet Farmer, and Jens Söring stayed behind to create the alibi, buying movie tickets for “Witness” and “Stranger than Paradise” (and watching the movies), and buying room service for two at the hotel. Hours passed, and there was still no sign of Elizabeth. Jens’ concern mounted, but also his frustration at Liz’s unreliability. At midnight, Jens bought one ticket to the Rocky Horror Picture Show and watched some of it, but returned to the hotel before it was finished.

Elizabeth arrived back shortly after 2:00 a.m. She was wearing different clothes than when she had left and was “white as a sheet, like she was in shock or something”. Her hands were clean, but Söring noticed a “brown smear” on her forearms. Elizabeth began repeated in a monotone: “I have killed my parents” Söring quotes her as saying: “It was the drugs that made me do it, and her parents deserved it anyway, and you have got to help me, if you don’t help me they’ll kill me, and I knew what she meant by that, execution”.

At first Jens didn’t believe the story, but she kept repeating it, and he finally accepted it. Jens knew he must protect Elizabeth, he “could not turn her in”. For the next four hours, Jens says, they discussed the situation. Eventually, the two agreed that the only way Jens could protect Elizabeth is by confessing to the murders himself. He would have to know something about what had happened. Accordingly, “we spent the rest of the evening talking about exactly how I would have done it and what for me to tell the police to make the whole story believable”. Jens cited his intense aversion to capital punishment as his motive for agreeing to take the blame for Elizabeth’s crime:

[T]he only thing that comes to mind to anybody when you think of being German is World War II and the holocaust [sic], okay? And that is something that’s drummed into German school kids, it was drummed into me, the two main conclusions from that, there must never again be war from German soil, and secondly, the worst and absolutely worst form of murder is if a government kills people in the name of its citizens, all right, which is what execution is, all right? Now again, I understand that people may feel differently here, but that’s a general feeling in Germany, and it’s a personal feeling, because I mean my grandparents’ generation were there, okay? And you know, if affects me personally as a German, it’s just as important to me as the idea of freedom is to Americans for example, okay? And you know, it’s important to understand that…

[I]f I had turned Elizabeth in, all right, and become part of the process that would lead to her execution, that to me, all right, would be myself becoming a murderer, not just a murderer, but the worst form of murderer, okay, because that’s basically exactly what happened 50 years ago in Germany, people turning other people in and the government killing them. And as a German, I just simply couldn’t do that, okay? That’s, I mean -- that’s what it means to be German to me, anyway.

Neaton then asked whether Jens realized he might face execution himself. Söring said he believed back then that his father’s diplomatic position might protect him. Although Jens realized “strict diplomatic immunity” doesn’t exist anymore, it was still common “amongst industrialized countries” that a foreign national with diplomatic immunity, after being arrested in the host country will be transferred to their own country of residence to stand trial. If he were tried in Germany, Jens told the jury, he would “spend five years in jail over there as a sentence, because that’s the maximum for 18 years olds over there.”

Neaton then turns to the beginnings of the relationship between Jens and Elizabeth. Jens describes himself as a shy teenage virgin captivated by the worldly Elizabeth. Neaton then brings up the Christmas Letter. Söring says: “Yes, I did write that, right. I mean some people smoke pot, some people get drunk, and I write long, boring letters.” Jens describes several passages as “[S]elbstgespraech. It’s a word in German that means having a conversation with yourself, all right. There’s nothing weird about it, it’s just a way of bringing ideas out and putting them down on paper.” Neaton takes Jens through all of the seemingly incriminating passages of the Christmas Letters. In rambling monologues, Jens explains all of these references away as harmless fantasies, figures of speech, jokes, and “bullshit”. Söring says: “98 percent of these letters is long, boring rambling about myself and books about philosophy that I have read, and art and nonsense like that, okay? Basically naval [sic] gazing, all right?”. The “ultimate weapon” he was going to use against her parents during the “famous dinner scene” was merely “love”:

[W]hen they see how much, you know, we love each other and how great our love is, all of your problems with your parents will be swept aside and they’ll basically take me into the family, write me into their will so they can leave me all their loot. There’s no question of killing them for money or anything, there’s just a question of meeting them and them accepting me into the fold, which is something she was worried about, because she felt her parents were always interfering in her life.

Other “weapons” Jens referred to were psychological techniques. Jens suggested: “Maybe I should expand on hypnosis and neurolinguistic programming,” surely the only time that sentence has been uttered by a defendant in a murder case. For the next three pages, he fulfills his promise, talking about “ideology bombs” which can cause massive opinion shifts and about subliminal messages in department-store music tapes which reduce theft.

Neaton eventually reins in his witness, turning to the next incriminating passage in the Christmas Letter, the sentence about a burglary which has gone wrong, and the “unfortunate owners…” Söring’s explanation for this is uncharacteristically blunt. It means “[e]xactly what it says. I mean if you hate your parents that much, maybe you’ll be lucky and they’ll get burgled. And if you hate them so much that you want them dead, maybe they’ll die that way, that’s all that said”. Asked about references to voodoo, Söring goes on another digression about where voodoo originated, whether it has a scientific basis, and what real-world effects it can have. Asked about “crushing” and “killing”, Söring explains he had just “just got through reading two excellent articles on World War II and its ending”. By this time, even Söring seems to have gotten tired of his own explanations: “Q: And then you go on for what, four or five pages writing about that? A: Right. I mean what I am — do we need to discuss this? Q: The jury can read that.”

After a break, Neaton turns to early 1985. Söring denies that the couple ever discussed killing the Haysoms or that he threatened to “blow their bloody heads off”. Turning to the March 1985 Ramada Inn letter Elizabeth had written during spring break, Söring says “what mostly stuck in my mind was the final two pages in which she did this long confession about having lied, and how terribly, terribly sorry she was, and she’d never do it again and all this nonsense.” After Elizabeth returned from her father’s birthday party in March 1985, Söring adamantly denies there was any talk of allowing Elizabeth to study in Europe, since that was the “last place [her parents] wanted her to go” because the last time, “she got into a lot of trouble with drugs and things like that”.

Söring denied having any bruises or bandaged fingers at the Haysoms’ funeral, and his lawyers introduced a photograph of him purporting to show that he blushed easily, and that some observers might confuse this with a bruise. Neaton turns to the 18 April letter, in which Elizabeth Haysom responded to Söring’s threats to turn himself in or commit suicide. Söring waved this away as a “massive failure to communicate, her misunderstanding a lot of my unqualified statements.” Turning to Elizabeth’s reference to Söring’s “sacrifice”, Söring insisted it meant his promise to confess:

I had agreed on that weekend, on the Sunday [31 March] to sacrifice five years of my life basically, to save her life, okay? And I mean, going out and killing two people is not a sacrifice. All right? Agreeing to take the blame for it is a sacrifice. And it’s pretty obvious to me, and that’s what I was referring to.

Söring then describes Elizabeth’s visit to his parents’ home in Detroit in early summer 1985: “My parents didn’t like her at all.” The couple took a European vacation, then returned for the fall semester at UVA, where they lived in separate housing.

When Ricky Gardner started asking to speak to Söring in late September, “we were both extremely worried” because it was obvious the detectives had not believed Elizabeth’s “cock and bull story” to explain the excess mileage on the rental car: “[I]t was clear to us that we were going to get arrested soon, they were going to figure it out, that we were involved.” According to Söring, Elizabeth gave her blood sample and footprints because “there would be no forensic evidence at the house to link her” to the crime. Söring was nervous because although he had agreed to confess if arrested, “the whole point was we were going to put that time off as long as possible”. Neaton asks Söring the obvious question of why he refused to give police forensic samples if he were innocent. Here is Söring’s response:

At that point we had already decided we were leaving, all right, and for something this big, what we assumed was that we would basically have to live underground and go into hiding kind of thing and live underground for the rest of our lives. And I did not want these people here to have any records of me if I could possibly avoid it. And that is why I said in the diary that I wiped fingerprints off the flat and my car, okay? Because if you think about it, at that point after we had left, by leaving, okay, we had already advertised our guilt to the world, all right, in that sense. So there was no point in wiping fingerprints away from a flat because if they had the fingerprints there to match, it wouldn’t have been any difference. By our leaving, we were already telling them, you have got the right people, basically. And the reason I wiped away fingerprints from the flat and from the car was because I was worried about them getting any fingerprints of mine which at some later stage in our lives if we got arrested could be used to, to link me back to this business here in Bedford.

Söring seems to understand that he has no good answer to this question, and, in his typical way, keeps adding excuses and explanations in the hope that the sheer quantity of words he has spoken will convince his audience.

Neaton skips over the trip around the world and comes to the London interviews. Söring says he lied during his London interrogations to save Elizabeth from the electric chair, as per their agreement. Söring does not repeat his March 1990 accusation that Kenneth Beever threatened Elizabeth. The only hint is in the following exchange: “Q: And were there any other reasons that you made these statements? A: Well, I mean there was concern of mine that she might come to some immediate physical harm, and you know, I didn’t know any better.” The jury must have been mystified. Be that as it may, this was good lawyering by Neaton and Cleaveland: If Söring had accused Beever of threatening Elizabeth, that would have “opened the door” for the prosecution to point out that Judge Sweeney had already concluded Jens Söring had lied under oath about the matter, shattering Söring’s credibility.

Söring then turns to the “mistakes” in his confessions, which would later feature prominently in his innocence narrative. He points out that the sketch he drew for the detectives shows Derek Haysom in the correct position, but not the correct orientation. Söring says he was concerned about the voodoo allegations because if the authorities believed them, authorities would “in Germany as well, throw you in a mental hospital and throw away the key”. The story that someone had mutilated the bodies after the murders came from Elizabeth. Söring claims Elizabeth wrote this to him in a letter in which she

said that the house was different from when she had left it, that somebody else must have come after her, and that’s what I was supposed to say, okay? And the person that she suggested to me was -- am I allowed to say the name? A close friend of the family she said was the person who must have come to after her to the house, and that was what I was to say as well.

In this letter, Elizabeth told him there were “waxed altars” and “African masks” found in the house and the bodies had both been posed to point in the same direction. When asked what had become of this letter, Söring, the self-confessed “hoarder”, said he had thrown it away because it was a “very dangerous” letter which “made it quite clear that she killed the Haysoms”.

Turning to the 30 December 1986 confession to the Bonn prosecutor, Söring claimed that his German lawyer Andreas Frieser and Neaton (who had already been hired by this time) had told him he needed to repeat his confessions to a German prosecutor to ensure he would be charged in Germany. His German lawyer told him to emphasize alcohol and Elizabeth’s manipulation because “[t]hose are mitigating circumstance in German law”. Neaton has Söring show his hand wounds to the jury, which were now barely visible. They were “[a]bsolutely not” knife scars, Söring assured the jury. One was a scar from a childhood accident with a marmalade jar, and the other was “a wart”. Neaton then introduces a letter dated 6 August 1986 from Elizabeth to Jens to help prove that Elizabeth is a “pathological liar”, which contains the sentence “I promise not to write anything definite and since my psychosis makes me lie pathologically and forget huge segments of history, I don’t think it matters what I write.”

Jim Updike now began his cross-examination of Söring. “Q: You admit that you have the capability of lying to protect yourself, don’t you? A: I suppose so. Q: You suppose? A: Yes.” Updike accuses Söring of being motivated by a desire to “beat these charges”; Söring insists he only wants to “tell the truth”. Updike then points out that Söring has had four years to prepare his story, and has also been provided with hundreds of pages of case documents. Updike then cites a prison letter from 22 October 1986 in which he assures Elizabeth his “American connections” will help him: “[M]y optimism is well founded, sweetie, remember, I’m always the pessimist, not you. Those yokels don’t know what’s coming down.” Updike asks: “Q: And you still think we don’t know what’s coming down, don’t you? A: Absolutely not. I don’t think you do, that’s correct, yes. I mean to put it bluntly, I don’t know how you can believe me.”

Updike then leads Söring through all the incriminating statements in his letters, letting Söring give his explanations of what he says they meant. Updike refers to the frequent statements in Söring’s confessions that he “hated” or “resented” the Haysoms:

Q: That there was resentment and anger building up in you, not only the night of you going to Loose Chippings, but in the months ahead of time?

A: That’s what I said in the statement, correct… And one of the problems that we have is that we had to convince —

Q: That’s not my question to you, sir. Then my question to you remains the same. You came to hate these two people because of what Elizabeth told you?

A: I think I came to sympathize with Elizabeth’s resentment. I didn’t hate them myself, I didn’t have any reason to hate them.

Why did Söring say he had come to “hate” the Haysoms, rather than simply “sympathize” with Elizabeth? Söring responds:

Because I was trying to convince the police to make them believe I did it; I had to give them some sort of motive , didn’t I?... That’s where the yokel remark comes about, I was amazed that you all believed me. I mean I couldn’t even tell you where the bodies were, and you believed me. I just don’t understand that. I mean it’s Elizabeth’s fingerprint in the house and you still think I did it.”

Updike continues:

Q: It’s your footprint there, too, isn’t it, Mr. Soering?

A: Well what does it mean, it’s a —

Q: It’s your blood type there as well, isn’t it, Mr. Soering?

A: 45 percent of the people have O type blood.

Q: 45 percent of the people, half the population, though, don’t have O type blood, and their footprint is there, and they admitted to doing this either, now did they, Mr. Soering?

A: That’s not my footprint.

Updike spars further with Söring about the meaning of his statements in his letters and diary and interviews. Then Updike targets the 30 December 1986 confessions. By that time, the relationship between Jens and Elizabeth had collapsed. Why did Söring not come clean and explain that he had been lying all along?

A: It was too late at that point, I had already said all these things in all these statements. I mean its pretty clear that by December ‘86 I didn’t love her anymore.

Q: You had [the extradition papers], and most certainly your attorneys had them in December of 86 when you made the statement to the Germans.

A: That’s right. And at that point --

Q: And you still continued, didn’t you?

A: That’s right, because that was the only way to get to Germany.

Q: You still continued with this statement exactly what you did.

A: It was the only way to get to Germany.

Q : Only way you could get to Germany.

A: Right.

After more exchanges about the letters, Updike turns to the weekend of the murders:

Q: So you all go to Washington. And I’m interested in what you’re saying now that the alibi was all about. First of all, you do agree that an alibi was prepared in Washington DC?

A: That’s correct.

Q: So you are in agreement with Elizabeth Haysom there?

A: Well I mean that’s what I thought….I thought I was part of the of the conspiracy to commit murder, That’s why I accepted, it was something we did.

Q: The Washington trip was an alibi, yes?

A: No. The trip wasn’t, no.

Q: While in Washington, did it become an alibi, was it an alibi?

A: Sure, on Saturday afternoon.

Updike then asks whether Söring would be present when Elizabeth delivered the “drugs” in Charlottesville on Sunday, 31 March 1985. Söring suggests maybe he might be.

Q: I thought you said that that Elizabeth had said that you were the type that would cause suspicion of a drug dealer?

A: That’s correct, but I knew Jim Farmer.

Q: You’re getting confused, aren’t you, Mr. Soering?

A: No you are, because you’re trying to confuse the jury. [Söring smiles]

Q: I want you to explain to me. Is this funny Mr. Soering? You’re on trial for first degree murder, two counts of it.

A: That’s right.

Q: Is it humorous to you? It’s not to me, is it to you?

A: No, of course not. Mr Updike, I did not know –

Q: Is this a game?

A: -- the drugs were in Washington, D.C

Q: Is this a game to you?

A: Of course not.

Q: Is it an intellectual challenge for you?

A: No, it isn’t

Q: It certainly wouldn’t be a challenge to you with your intellect to outwit me, would it?

A: Well I think so far you have been outwitting me.

Q: I just don’t understand why you at times are sitting up there under these circumstances on trial for murder laughing.

A: I’m not laughing.

Q: Haven’t you laughed, didn’t you laugh just a few minutes ago?

A: I smiled because you were trying to mislead the jury.

Updike next attacks the alibi story. Söring admits “we didn’t discuss Loose Chippings before she left” at around 4:30 p.m. on Saturday, 30 March 1985, to murder her own parents. But then why did he set up an alibi for her in Washington?

Q: You would have to say that you were providing an alibi for Elizabeth to commit the murders at Loose Chippings, wouldn’t you?

A: But I didn’t even know about that.

Q: I’m asking you if you had said that.

A: (witness shakes head in the negative.)

Q: And if you had said that, Mr. Soering, then you would be admitting guilt to the same thing that she had to admit guilt to, and that was an accessory before the fact wouldn’t you?

A: I’m sorry, you have lost me.

Q: You’re smarter than I am.

A: If I were to admit that I would provide an alibi for her if she were to kill, that would make me an accessory before the fact?

Q: Right.

A: Yes, I guess so, yes.

Q: Yes, you guess so.

A: (Witness nods head in the affirmative.)

Q: And you don’t want that, because you want to beat this thing completely.

A: It’s not what happened.

This important exchange highlights a theme Updike would return to. Elizabeth, whatever her motivations or credibility, was willing to plead guilty to being an accessory before the fact to murder, which exposed her to a potential life sentence. Now Söring is telling a story which is essentially the exact mirror-image of Elizabeth’s: He stayed in Washington while she killed her parents.

However, Söring isn’t willing to accept responsibility for his role the way Elizabeth was. He is only willing to admit to being an accessory after the fact, which carries a much lighter sentence than accessory before the fact. In Updike’s words, Söring wants to “beat this thing” (i.e., the charges), completely and walk out of the courtroom a free man. Söring used his four years of preparation to carefully construct an alternate version which absolves him of any legal or moral responsibility for the murders. For Updike, this was too convenient by half.

Updike now turns to the movie tickets. This subject can be tedious, but a brief rundown is necessary, since the subject comes up again and again – and was also responsible for the peak moment of courtroom comedy in this otherwise grim trial. As we’ve seen, both Söring and Haysom had previously called their plan to forge an alibi by purchasing pairs of tickets for various movies “idiotic”.

In 1985, before computerization, movie tickets did not show who purchased them, when, or what movies they were for. Indeed, we don’t know whether they were bought by Söring or Haysom. In 1985, tickets for movies were “validated” by simply tearing them in half; after the movie, many theater patrons simply threw the tickets stubs in the nearest trash can. Anyone could have reached in and plucked a handful from the among the candy wrappers and drink cups. It is thus no surprise that both Söring and Haysom, in their previous statements, had ridiculed the idea that the movie tickets proved anything.

However, Söring now claimed they proved his innocence. Let’s review the background: In early April 1985, Haysom and Söring were concerned they might need to show the authorities proof they had stayed in Washington, D.C., the entire weekend of 30 and 31 March. They dictated their activities over the weekend to Elizabeth’s friend Christine Tan, who wrote them down in a brief “alibi timeline” covering all of their weekend in Washington (all parties concede this timeline was inaccurate, and it played no role in either trial).

Jens had also kept some of their receipts from the trip, including movie tickets. These movie tickets consisted of two tickets for “Porky’s Revenge”, which they both watched on Friday, 29 March 1985, two tickets each for “Witness” and “Stranger than Paradise”, for showings on Saturday, 30 March, and one ticket for “The Rocky Horror Picture Show”, which showed at 12:00 midnight on 30 March. The defense had introduced these 5 tickets (2 each for Witness and Stranger than Paradise, and one for Rocky Horror Picture Show) stapled on a piece of paper with Jens Söring’s handwriting on it.

How did these tickets end up so neatly presented on one piece of paper? The story is obscure and conflicting; Terry Wright explores it at length. To sum up, it appears that John Lowe, the attorney for Elizabeth Haysom, obtained this piece of paper with the tickets on it (or a copy of it) sometime in 1985. He soon left the case, but the tickets remained in his possession. After Jens and Elizabeth were arrested in 1986 Jens’ lawyers, including Richard Neaton, obtained the tickets, probably from Lowe.

The tickets were not an issue during Haysom’s trial, since she did not claim the tickets proved anything. During her testimony at Söring’s trial, however, the tickets were somewhat more important, since they could provide weak corroboration for Elizabeth’s claim she stayed in Washington, D.C. on 30 March. Jim Updike therefore went on a search for the elusive tickets, and finally obtained a photocopy of them. Meanwhile, the defense had possessed the originals the entire time.

Johann Söring, for his part, testified during his son’s trial that he (Johann), had discovered these tickets among Jens’ possessions after Johann had visited Charlottesville in early December 1985 to clean out Jens’ apartment after he had fled the country. Johann testified that the tickets were lying around loose in an envelope, and that Johann himself attached them to the piece of paper and photocopied them.

This conflicts with other testimony showing the tickets were already circulating in this or a similar form in April 1985. Further, if Johann only attached the tickets to the piece of paper in December 1985, when Jens had already left the U.S., it is difficult to explain how Jens’ handwriting appeared on the piece of paper next the Rocky Horror ticket: “3/30 Rocky Horror Picture Show”. Perhaps there is an innocent explanation for this discrepancy. Terry Wright, who illuminated this interesting aspect of the case for the first time, concludes charitably: “Perhaps [Johann] was doing what many fathers would do, trying to be truthful, and yet, at the same time trying not to say anything that might incriminate his son.”

In any event, now, at long last, all parties to the case could actually see the tickets Jens or Elizabeth had bought. Updike was curious about a number of things. First of all, Söring had kept tickets to his meal with Elizabeth at Hamburger Hamlet and the tickets to “Porky’s Revenge” on Friday night. Yet according to Söring’s story, he didn’t even know on Friday that he would need to create an alibi in the first place.

Why did he keep these receipts? Söring responds: “Well, unfortunately Elizabeth and I – well I was a hoarder, if you want to call it that. When I was arrested in England, they arrested us with this gigantic big folder –” Updike cuts him off here. Even when testifying before a jury with his freedom in their hands, Söring cannot resist castigating himself for keeping so much incriminating evidence.

Updike offers the logical alternate explanation: Söring kept all these documents because he “wanted the entire weekend to be an alibi to cover up your activities”. Söring then claims the Friday evening tickets were irrelevant. Updike pounces again: “I don’t understand why a man keeps tickets to a movie for better than five years, can you explain that to me if it doesn’t mean anything?” Söring replies: “I didn’t. Actually we left them behind in Charlottesville. They were forgotten. That’s where my father found them. I didn’t keep them.”

The rest of the exchange veers into the farcical:

Q: Your father turned [the tickets] over to your attorneys in December 1985?

A: Right.

Q: And the first that anybody other than you or your lawyers have seen any of these tickets, the originals, was today?

A: That’s right.

Q: And you claim that these tickets are an alibi for you, or excuse me, establish your innocence?

A: That’s correct, yes.

Q: I have a little difficulty understanding, perhaps you can help me, Mr. Soering. If you have got evidence that you feel will establish your innocence, why are you sitting in jail over there for such a long period of time since April 1986 holding and having control over evidence that you feel will establish your innocence?

MR. NEATON: Objection, he assumes facts not in evidence; Mr. Soering did not have control over those tickets when he was in England.

THE WITNESS: I didn’t actually know about them.

MR. NEATON: Shut up.

MR. UPDIKE: I couldn’t say that.

MR. NEATON: Well, he’s my client and –

MR: UPDIKE: And I’m not criticizing you for saying it, I encourage him to say it any time he wants.

Updike presses further. Söring has just claimed that he confessed to the murders only to protect Elizabeth from the electric chair. But Elizabeth had pled guilty and was sentenced in 1987. After that time, Söring could reveal his own “innocence” by means of the movie tickets at any time. Why didn’t he do so? Söring repeatedly claims he “didn’t know” they existed. Didn’t his own lawyers know about them? Didn’t his own father, Johann — who testified under oath that he found the tickets in December 1985 — ever tell him about the tickets?

Neaton, sensing danger, objects repeatedly to this line of questioning by citing attorney-client privilege and even the defendant’s right to remain silent, even though Söring had waived this right by taking the witness stand. Updike protests Neaton’s continued interruptions:

MR. UPDIKE: Your Honor, it’s a matter of common sense. Now he has been locked up for three years. We saw these tickets, the Commonwealth of Virginia, for the first time today. Now I have a right to ask this man [Söring] why it took so long.

MR. NEATON: This man didn’t know about the tickets until last year, as he’s already testified.

MR. UPDIKE: You were his attorney, didn’t you tell him?

MR. NEATON: No.

MR. UPDIKE: You didn’t tell your own client?

At this point Judge Sweeney, perhaps out of charity towards Neaton, calls a halt to the exchange.

Updike’s astonishment is understandable. Johann Söring testified earlier that he provided copies of the tickets to his lawyer in December 1985, shortly after finding them in Söring’s belongings. They were then sent to Söring’s own defense lawyers sometime in 1986. Yet if Söring is to be believed, for the next four years, neither his lawyers nor his own father ever told him that the tickets had been found. Nor did Jens Söring know they were available, even though the tickets are attached to a piece of paper which has his own handwriting on it. Yet Söring now cites the tickets as critical proof of his own innocence.

“Oh what a tangled web we weave,” Sir Walter Scott once wrote, “when first we practice to deceive.” The real story is simple. Söring’s plan as of mid-1985 was to claim that both he and Elizabeth had remained in Washington the whole murder weekend. To bolster this claim, Söring himself assembled the tickets stubs and attached them to the paper, adding his own notes. After he was arrested, both he and Elizabeth admitted the alibi was fraudulent, and the ticket stubs meant nothing.

That remained the state of play until March 1990, when Söring needed to change his strategy and claim he had remained in Washington, D.C. during the murders. Now he would claim he had bought the tickets and watched the movies. But this creates a huge problem for Söring, since now he has to explain why, if he had known of evidence of his innocence for four years, he had never mentioned it or shown it to anyone.

Söring himself set this trap, which Updike springs shut on him. Johann Söring’s testimony was supposed to bolster Söring’s account. According to Johann, Jens left the tickets behind in Charlottesville when he fled the country. Thus, Jens had no first-hand knowledge of where they were or who had access to them, explaining why the tickets never came up during the four years Söring spent awaiting his trial.

Yet Jens’ explanation is dangerous for both Johann and for Richard Neaton, since his story begs the question of why, for years, he never asked his father or his lawyer about evidence which he now claims proves his innocence. The value of the tickets as evidence was negligible. But the story of how they were used at Söring’s trial shows how readily Söring will change his story – even retroactively – when he believes it serves his interests. It also shows Söring’s ability to induce other people to help him establish his story. Both Johann Söring and Richard Neaton were willing to make questionable statements in court to try to help Söring.

Returning to the cross examination, Updike then asks Söring why Elizabeth would need an alibi merely for her drug run, and why movie tickets would be enough to convince someone who was skeptical of her account. Söring has no real answers for these questions and merely repeats that Elizabeth thought this was the case and Elizabeth told him to get the tickets.

Updike again focuses on the convenience of Söring’s current story. If Söring admitted that he knew Elizabeth was going to drive to Lynchburg and kill her parents, and agreed to help by creating an alibi, that would be an admission to being an accessory before the fact to murder, the same crime Elizabeth had pled guilty to. Söring admits this is the case. Updike then says: “And you don’t want [to admit] that, because you want to beat this thing completely”. Söring disagrees.

Updike then asks Söring why, if the movie tickets were so important, he didn’t mention them in his October 6 interview with Gardner and Reid. He says he couldn’t do that because police already knew about the mileage discrepancy on the rental car. Updike lets this non-sequitur stand and asks Söring whether he got a cup of coffee during the interview. Söring agrees he did. Updike then asks: “And you later became concerned that they would get your fingerprints off of that cup?” Söring answers: “No, I didn’t. I made a joke about it.” He would change this story later.

Updike asks Söring why Elizabeth gave her fingerprints on 16 April 1985 and her footprints and blood sample in September. Söring repeats the answer he gave on direct examination: “[S]he wasn’t worried about physical evidence because she said there would be none.” In that case, Updike asks, what was the risk to Söring of giving physical evidence? If Elizabeth, who personally butchered both of her parents, was not concerned about physical evidence, why would Jens, who wasn’t even there, object? Even if he didn’t want to give his fingerprints to avoid being tracked while on the run, his footprints and blood sample could hardly be used for this purpose.

Updike now turns to Söring’s London confessions. He notes that on the very first day, 5 June 1986, Söring told the detectives that the pair had discussed “murder” and that Elizabeth knew he was planning to confront and quite possibly kill the Haysoms. If his goal was to protect Elizabeth, why did he accuse her of a crime carrying a life sentence, when he could have simply said “I did it, Elizabeth Haysom had no involvement”? Söring responds that “we” (he and Elizabeth) did not think this would be possible: “We didn’t think it would be believable to say that Elizabeth was completely uninvolved for obvious reasons.” Updike gets Söring to confirm that he thought it would “make no sense” to argue Elizabeth knew absolutely nothing.

Q: But you, Mr. Soering, are now doing the same thing. You are saying that Elizabeth Haysom went to Loose Chippings and that you stayed in Washington and that you knew nothing about it and you had no involvement, so therefore your explanation makes no sense, correct?

A: That’s not true, no.

Q: It’s the same thing, only reversing roles….But it’s the same thing reversed, just changing the names. It made no sense in instance A, but you’re saying it does make sense to these ladies and gentlemen as it applies to you, with you as the alibi?

A: Yes. And I will explain that if you want me to.

Söring always has an explanation, but Updike was not interested in hearing it. Updike points out that on 5 June 1986, Elizabeth had refused to answer any questions, but Söring was already implicating her:

Q: This woman that you say you love so much, you were giving the police information to incriminate her on two counts of first-degree murder carrying 20 years to life on each. Now is that love, Mr. Soering?

A: That is correct. That was the only way I thought we could keep her out of the electric chair.

Q: Is that protecting her, Mr. Soering?

A: That was the only believable thing to say.

Q: You could have said that she had no involvement.

A: No, we couldn’t have, because in that case she would have to turn me in, obviously, if we said that that wouldn’t be believable.

Q: But it is believable – it’s not believable to say Elizabeth stayed in Washington with no involvement, but it is believable Jens Soering stayed in Washington with no involvement.

A: Well, they were not my parents.

Updike then gets Soering to admit he always refused to discuss the murder weapon because he was afraid it would prove premeditation: “[I]n that regard, you were not protecting Elizabeth Haysom, you were protecting Jens Soering”. Updike then hammers Söring on various changes in his story. During his extradition fight, he never challenged his guilt of killing the Haysoms, but now he is. Söring claims he proclaimed his innocence in 1989, but provides no proof. Söring also admits that in his 6 June 1986 interview, he said Elizabeth was not involved in drugs. He claims he was merely trying to “keep any sort of suspicion as far away…from her as possible.”

Shortly after this exchange, Judge Sweeney decided to halt proceedings for the day, since the air-conditioning had broken down and “it’s just getting unbearable in here”. The next day, Updike concluded his cross-examination by going through the most damning parts of Söring’s various statements and asking Söring about them. Over and over, Söring replied “That’s what I said” or “That’s what I told them”. Occasionally Söring adds extra details, many of which weren’t particularly helpful. For instance, when he’s asked what song was playing while he was sitting in the car thinking about how to clean up the evidence, Söring volunteered that it was “Psycho Killer” by the Talking Heads, even adding it was “first put out in 1977”. Söring tries to fit in excuses and explanations wherever possible, prompting Updike’s scorn: “Q: You’re right-handed, aren’t you? A: Yes, sir, yes. So is Elizabeth. Q: Thank you. Thank you for volunteering that.”

On redirect examination, Richard Neaton asked Jens a few more questions, and Johann Söring testified to some points about the tickets. And that concluded the evidence in the trial of Jens Söring.

Courtroom observers concluded unanimously that Jens Söring’s testimony had been a disaster. He came across as arrogant, condescending, and evasive. Söring shares this judgment, which is why he almost never mentions his trial testimony. Here is his entire discussion of his testimony from his 1995 book Mortal Thoughts:

[T]he defence opened its case, which was based almost entirely on my own testimony. As if that were not enough pressure, I also had to contend with a whole series of curious distractions while I told my story. First, the courtroom’s air conditioner broke down, and the temperature inside soon rose even beyond the extremes of the Virginia June heat outside. Then the lights began failing intermittently, plunging the whole court into darkness on several occasions. Strangely enough, the air conditioning and lighting systems experienced such problems only when I was testifying. Nevertheless, I managed to maintain my composure and give the jurors version of the events of March 30, 1985, as I have done here in Chapters 4 and 9.

This was all Söring had to say about the first time he revealed his new story and claimed his confessions were false. Typically, Söring inserts a complaint about the air-conditioning and an insinuation of conspiracy and foul play. Of course, Söring does not acknowledge that the lack of air-conditioning affected everybody in the courtroom, or mention that Judge Sweeney cut the proceedings short, citing the “unbearable” temperature.

Söring has ignored his trial testimony for 30 years, and when he does address it, he attributes its failure to stress, youth, and inexperience. He implies the jury voted to convict him because they disliked him – or perhaps, because they disliked Germans. But there is a simpler explanation: They thought he was lying. His attempt to cite the movie tickets as evidence of his innocence collapsed into farce. His explanations for his motives were incoherent and implausible, and his disquisitions to the jury on subjects such as warfare, Taoism, the death penalty, and diplomatic immunity could hardly have helped him.

After Söring’s cross-examination, his fate was sealed. When the defendant takes the stand in an American criminal trial, all other testimony fades into insignificance. Everything rests on this ultimate make-or-break gambit. If the defendant has convincing explanations for the evidence against him, he may be able to snatch victory – or at least a mistrial – from the jaws of defeat. If he does not, which is almost always the case, his inability to explain the evidence against him becomes the most powerful evidence against him.

The most devastating testimony against Jens Söring was delivered not by Elizabeth Haysom, but by Jens Söring.

Defendants in criminal cases face a cruel dilemma: Either stay silent, and watch the state’s evidence convict them, or take the witness stand, and let their incoherent answers add yet more incriminating evidence to the pile. The only escape from this dilemma is a convincing claim of innocence. Söring had none. The reason his testimony went so badly is that he was faced with overwhelming evidence of his guilt which he could not explain away.

The closing arguments went on for hours, recapping the main arguments of the trial. The jury retired to deliberate on 21 June 1990. The jury retired at 2:50 pm and returned its verdict at 6:35 pm, after deliberating for 3 hours and 45 minutes, which is short by the standards of American murder trials. The guilty verdict was unanimous, and the jury recommended that Söring be sentenced to life on each count. Each juror was “polled” in open court to confirm their agreement with the verdict. Söring was asked if he had a statement before the judge pronounced judgment. “I’m innocent,” said Söring. Before ending the court session, Judge Sweeney stated for the record:

The only other thing I would like to say is I would like to thank the lawyers on both sides. Both sides have been represented by professional, competent lawyers who have fought hard and fought fair, I don’t know of any case in 25 years in which I have seen better lawyers on both sides, and I appreciate that.

Söring appeared in court again on 4 September 1990 for his sentencing. The proceeding was not particularly important; the jury had recommended life, and Judge Sweeney was unlikely to second-guess them.

Söring’s family were not present; they lived far from Virginia and the hearing was something of a formality. Neaton read a prepared statement from the family. They acknowledged that the killing of the Haysoms was horrible, but they stated they did not believe their son was capable of such violence. The language they use is revealing: “He insists that he did not commit these horrible crimes.” Usually, supportive family members of the defendant emphasize that the defendant has never admitted guilt to them, which bolsters their convicted family member’s case: He has always maintained his innocence even towards his own family. The family merely states that Söring now insists he is innocent, which everyone already knew.

The family says they have refused to speak to the press because “because we did not feel our opinions mattered for anything but media gossip”. This may well be a cultural factor at play. Upper-middle class Germans tend to be mindful of their privacy, and it is almost unknown in Germany for crime victims to seek a high public profile. Nevertheless, their silence harmed Söring. Family members who believe their accused son or brother is innocent, as the Sörings claimed, are usually eager to prevent his wrongful conviction. They say of Söring: “Jens may have had a high IQ, but he was very foolish and naive in the practical aspects of life. Like most eighteen year old children, he believed that nothing bad could happen to him. He was very wrong about that.”

Söring’s family then complains about aspects of the trial they believed were unfair, including Judge Sweeney’s friendship with Risque Benedict and the fact that the trial was not moved to another jurisdiction. Jens, they admit, was wrong to call Bedford County people yokels “but it was not wrong for Mr. Updike to state that the Germans can ‘go to hell’ and imply that all Germans are Nazis?... We, our family and our friends were deeply offended by Mr. Updike’s comments.” Updike objects, challenging this claim as inaccurate and irrelevant. Söring would take up all of these complaints in his later appeals and writings, which suggests he may have had a hand in formulating the family’s statement. As with Söring’s myriad complaints about his trial, these are side issues which portray Söring as a victim, but do not undermine the evidence used to convict him. The family concludes by asking that Söring be allowed to serve his time in Germany, another cherished goal of Söring himself.

Updike tells the court he has nothing to add: “The jury has heard all the evidence. There was a lot of evidence. That was a long trial. The case was tried fairly and a fair and impartial decision was rendered and a just punishment was fixed by the jury.” Updike opposes transferring Söring to Germany, since he would likely be released in a few years. Updike requests two consecutive life sentences. In his conclusion, Updike notes Söring’s tendency to complain about every aspect of his treatment while ignoring the evidence against him:

[T]hroughout this matter, from the very beginning of the proceedings in January … there has been an effort [by the defense] to talk about everything except the evidence. Should there be an appeal… the Commonwealth stands prepared to argue the facts In the record. We are prepared to deal with that, The rest of the criticism and the innuendos, I’m tired of it, and I’m not going to waste anymore of my time to respond to it. We ask that Jens Soering, on both convictions of first degree murder, he sentenced to life imprisonment.”

Neaton then gives a short statement to the court. He tells the court that he has gotten to know Söring extremely well “since 1986”, and that he finds it “inconsistent with [Söring’s] character as I have come to know it that he would commit a crime of violence”. Neaton then obliquely addresses the bad impression Söring left during the proceedings:

What people may perceive as arrogance, abruptness, what some may perceive as not being interested in the proceedings, is really just a kind of stoic behavior pattern that I have found to be consistent with a lot of German people, from the section of Germany that he and his parents are from… the Jens Soering I know is a caring, feeling human being and does have emotions.

Neaton then points to the fact that Söring has been in prison for four years, that his cross-examination was “very trying”, that no matter which theory one believed, he was a young man under influence from young woman with a very strong personality. Neaton asks the judge to impose the same sentence on Jens as on Elizabeth: 45 years.

Judge Sweeney then gave a brief statement. He refused to state his opinion of the evidence or of Jens Söring’s character, but said he believed the trial had been fair. The jury had paid attention and taken its duties seriously. Judge Sweeney had given the jury the option to convict Söring of second-degree murder (maximum sentence 20 years) if they felt alcohol intoxication had rendered him incapable of premeditation. Instead, they concluded that Söring had committed the crime in a premeditated manner, convicted him of the maximum charge, and recommended the maximum sentence: “[A]fter a full consideration of the pre-sentence report, the arguments of counsel, and my own conscience, I have decided to approve the jury verdict and not disturb it.” Sweeney then adds that in light of Söring’s youth, Sweeney will recommend that Söring be placed in a special prison for youthful offenders, “where he could be safe, at some location where his talents can be built upon, where there can he some degree of rehabilitation”.

Asked whether he had any comment before sentence was imposed, Söring repeated: “I’m innocent”.

Ich bin gespannt und freue mich auf die deutsche Version des Buches! Beste Grüße!

"Updike lehnt eine Überstellung Sörings nach Deutschland ab, da er wahrscheinlich in einigen Jahren entlassen würde. Updike fordert zwei aufeinanderfolgende lebenslängliche Freiheitsstrafen."

Ist ersteres tatsächlich eine juristisch zulässige Begründung, jemanden nicht auszuliefern? Updikes Ablehnung impliziert doch indirekt, dass man das deutsche Strafrecht für unzulänglich hinsichtlich der hier üblichen Strafen hält. Hatte Deutschland überhaupt einen Antrag auf Auslieferung gestellt?